Transcript

Mrs. Rupp began our afternoon lesson in fifth grade the same way she began the morning one—pulling out a compact mirror and ducking behind it to daub her lips a few times before sitting down at her desk. Mrs. Rupp had bleached blond hair cut to her chin, and she often fixed it around her face with long fingernails that matched her lipstick. In 1968, with her skirts above the knee, she might have fit right in at someplace like New York, but in our tiny farm town in Ohio she most certainly did not. Mrs. Rupp had “married in,” as the locals said.

On this day Mrs. Rupp had the job of introducing us to Robert’s Rules of Order. Did she tell us why—because most of the groups and organizations we would grow up to join made their decisions this way? I don’t recall, likely because I was already long gone from the room, my mind wandering to whatever book I was reading at the time.

So when I heard Mrs. Rupp call my name, it came as a shock.

“Come on, Priscilla, sit up here,” she said in her nasally city drawl, pointing with a bubblegum pink finger at the bar stool she’d set up next to her desk. “We’re going to hold a meeting.”

I dragged myself out of my desk and perched on the stool, having no idea what she was talking about.

Mrs. Rupp walked the class through the steps of a simple group discussion. She gave us a topic to talk about. She coached me to ask the group for a motion then a second. She prompted me to recognize speakers. At some point we took a vote. And finally she released me to go back to my desk.

I sank back down, reeling. What was that all about? To me the whole thing felt pointless. Empty. Awkward! So artificial I couldn’t believe any adults actually put up with it.

And why in the world had she called on me? At that time we didn’t know about autism and the howling discomfort of being perched up in front of a class with all eyes on me. We didn’t know that I felt so jangled by group discussions that when I grew up I would need to work alone from home my entire life. I was a stellar student, so it may not have been entirely obvious that I was about as suited for running meetings as I was for, say, performing circus acrobatics.

I did get one thing out of the lesson, though I doubt it was the intended thing. I learned I wanted nothing to do with Robert’s Rules of Order ever again.

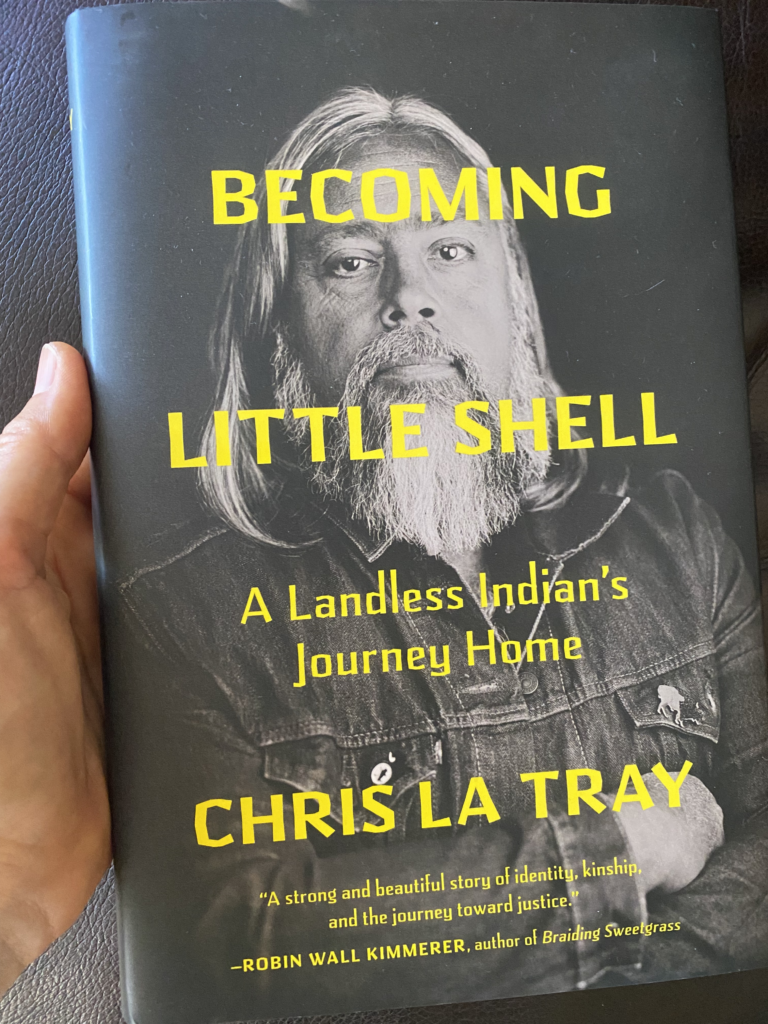

That afternoon from fifth grade suddenly came flashing back while I was reading Chris La Tray’s beautiful new book, Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home. Chris is the Poet Laureate of Montana, and in his memoir he outlines a history I had never heard before—of the Métis people of the upper plains. How in the 1600s the Native women of the Cree and other tribes met up with French fur traders and introduced them to Native cultures. How the women acted as guides for the traders, married them, and made new families with them. How their descendants developed ways of life that were not Indian, not European, but something altogether their own. They invented their own modes of transportation, their own clothing styles, their own languages in a blending of European and Indigenous ways. Chris lays out the fascinating history, especially as it relates to one branch of his family tree, the Little Shell band of the Chippewa Indians.

And it was something Chris wrote in his story of coming home to his Little Shell roots that kindled my memories of fifth grade. It was only an aside, almost an offhand comment, about tribal leadership. In the mid-1800s the chief Little Shell was leading his Chippewa and Métis people through those treacherous decades of having their homelands stolen out from under them by an American government that was greedy to give the land to settlers. Little Shell had to negotiate treaties on behalf of all his people. He had to lead this sizable group toward agreement, and he had to do it, Chris says, by persuasion because the tribes did not operate from the top down.

“There weren’t any ‘Robert’s Rules of Order’ protocols in place,” Chris writes, “like what I suffer through whenever I attend a tribal council meeting. That’s a colonial form of leadership,” he adds, and Little Shell’s Chippewa people “didn’t operate like that.”

And there went my mind, taking off in a rush, flowing right back to fifth grade.

And what does all this have to do with honeybees? We’re getting there, I promise!

![]() The lesson I learned in fifth grade stayed with me. To this day I avoid city council meetings, with their motions and seconds; I send public testimony by email. The groups I’ve been a part of made their decisions in other ways, usually by consensus. We wanted every person’s voice to matter. We knew that majority votes often polarize a group, and we couldn’t afford those conflicts.

The lesson I learned in fifth grade stayed with me. To this day I avoid city council meetings, with their motions and seconds; I send public testimony by email. The groups I’ve been a part of made their decisions in other ways, usually by consensus. We wanted every person’s voice to matter. We knew that majority votes often polarize a group, and we couldn’t afford those conflicts.

So when I read Chris’s little aside—that Robert’s Rules is a colonial form of leadership—a light clicked on. The process came from conquerors. I mean, it’s literally true—it’s based on rules of Congress, which themselves come from those of the British Parliament, with their roots in Anglo-Saxon law.

But Robert’s Rules are colonial not just in history but in style and content as well. I was thinking about all this when, in one of those bits of everyday magic, an essay crossed my desk out of the blue that offered a theory why. The essay is by the late David Graeber, and it appears in a new collection of his essays coming out next month called The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World. The title comes from one of Graeber’s most famous sentences: “The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.”

And right there in the title is the thing I value so highly about David Graeber: his relentless eye for possibility. His bone-deep knowing that things could be otherwise—that all the systems of power in our world, all of them looking so massive and immutable, are really just decisions that some set of people made at some point in time, and that we, at this point in time, could do differently.

We can choose otherwise.

I clicked on the book sample and found Graeber talking about why majority rule has more of tyranny in it than community.

He says majority rule depends on the threat of coercion.

Think of it this way, he suggests: The small face-to-face communities that humans have always lived in likely didn’t make decisions by majority vote because there was no way to force a minority to accept the majority decision. He writes, “If there is no way to compel those who find a majority decision distasteful to go along with it, then the last thing one would want to do is to hold a vote: a public contest which someone will be seen to lose.”

But when the state appeared, with its coercive military force, as in ancient Greek city-states, majority voting appeared at the same time. The men of a Greek city-state were also its fighting force, all of them very well armed. When they took a vote on public affairs, each side could see the weapons of the other side waiting. In such a climate, Graeber says, “every vote was, in a real sense, a conquest.”

Many groups today are making their decisions in other ways. In more inclusive ways. People are now embracing what the honeybees have known since forever.

![]() But before we get to the bees, one last point about Robert’s Rules.

But before we get to the bees, one last point about Robert’s Rules.

The man who wrote the rules, Henry Robert, apparently loved order above all else. Through the wrenching years of the Civil War, he came to believe that democracy could survive only when losers of a vote submit to the winning side. And they must do so gracefully and cheerfully, he said, until they can win support for their own side.

It’s a point that is often repeated today, but whenever I hear it I feel a tension rising in my belly, a little squelching of the spirit. And for good reason. Robert’s love for order came, as he himself said, from a belief that appears often in Western thinking: the idea that individual freedom is at odds with the common good.

Here’s what Robert wrote in his preface to the rules: “it is necessary to restrain the individual somewhat, as the right of an individual, in any community, to do what he pleases, is incompatible with the interests of the whole.”

It might seem obvious that individual rights need some sort of check, but it is important to say that not every society buys into this opposition. In African thought, for example, there is no basic tension between individual and community. The Ghanaian sociologist George Sefa Dei says that in African thought individual and community enhance each other, and individuals are “enriched by community.” The community trusts its members, in other words, and offers them love and support in order to bring out the gifts of each person.

Societies such as ours that start with an opposition between individual and community tend to give the state the job of being an authority over individuals. This is the undertow of authoritarianism that has tugged at Western societies since at least the time of the authoritarian Roman Empire, and it is tugging at American society right now.

For us it has its roots in the ancient Greek idea that the body and soul are separate—that the body acts out of passions while the mind or soul operates by reason. Plato said it was like a chariot powered by strong horses: the horses are the passions, charging forward wildly. So the mind, or reason, has to be the charioteer, keeping a tight hold on the reins.

This Greek dualism formed the bedrock of thought throughout the Roman Empire and then deeply shaped Christian thought as well, especially when Christianity became the religion of the empire in the fourth century during the decline of Rome. The most well-known thinker of that time, Augustine, taught that humans are sinful creatures, so tainted that we’re unable not to not sin. It’s his famous doctrine of original sin, and it has much of Plato’s chariot in it—except now the horses are all of humanity, all of us charging forward willfully, needing some moral force to hold the reins. In Augustine’s time, while the central political power was crumbling, the church stepped into that role, grabbing the reins of society in order to steer a good moral course. Augustine’s vision of sinful people guided by a holy church would go on to power Europe for a thousand years.

As the modern era was dawning, European thinkers rejected the power of the church, but ironically they held onto its central idea: that human nature is depraved. For example, Thomas Hobbes in the 1600s wrote that individuals are so selfish and violent that they will destroy one another in “a war of all against all” unless there is a central state powerful enough to keep them away from each other’s throats. It was a terribly jaundiced vision of human nature, and in fact of all of nature—as if selfishness and violence lie at the core of nature itself—and most of Hobbes’s contemporaries were horrified by it. But after his death, as capitalism took hold and its cruelties multiplied, Hobbes began to look like only common sense. Two hundred years after Hobbes this idea of selfish individuals fighting to take resources from others was so widely accepted that when Darwin was trying to figure out how natural selection actually worked, he settled on the idea, derived from Hobbes and others, that it is driven primarily by competition in the struggle for existence.

What a negative view of ourselves running down through the centuries! From human nature as willful (in Plato) to human nature as sinful (in Augustine) to human nature as fundamentally selfish and violent (in Hobbes). No other people on Earth hold such a pessimistic view of themselves. The cultural anthropologist Marshall Sahlins once wrote, “So far as I am aware, we are the only society on earth that thinks of itself as having risen from savagery, identified with a ruthless nature. Everyone else believes they are descended from gods.”

So, finding a ruthless nature in ourselves, we of course “found” it in the natural world as well. We have been quick to spot fierce competition among other creatures and slow to recognize when they cooperate and show respect.

And we’ve been especially slow to see democracy among the animals.

Which is where the honeybees come in at last!

Honeybees are skilled in group decision making, and I wish I’d been learning about their rules instead of Robert’s Rules in the fifth grade! But much of the work of sitting beside swarms for hours and days at a time and patiently counting and recording honeybee dance routines hadn’t even been done yet.

Honeybees are skilled in group decision making, and I wish I’d been learning about their rules instead of Robert’s Rules in the fifth grade! But much of the work of sitting beside swarms for hours and days at a time and patiently counting and recording honeybee dance routines hadn’t even been done yet.

It turns out that when a hive splits into two and one colony takes off to settle elsewhere, the swarming group follows a careful democratic process to choose their new home.

The swarm first flies out a short ways and then pauses to rest and wait, draping their thousands of bodies across a branch in a thick cluster that looks like a massive beard. While they wait, a portion of the group, hundreds of them, take off to survey the area.

A scouting bee may find a nesting cavity that meets all her specifications, and she right away flies back to the swarm and dances across their clustered backs to report on it. In her dance she lays out the map to the spot she has found so others can check it out too. If it is an especially attractive cavity, she dances vigorously and long, repeating the directions over and over. If it is kind of meh, she might dance only a little.

As the hours pass, more scouts return with their reports—a pretty good new home in this direction, an excellent one in that direction, maybe a dozen or more possibilities all told. A bee who didn’t find anything on her first round might return to find a sister dancing vigorously for a site, so she’ll fly out to inspect the site for herself. If she likes it too, she’ll come back and dance for that site. New scouts join in, visiting a site and adding their opinions. The scouting and dancing continue for two or three days, and the possible new homes gain and lose supporters. Gradually support for one site builds and support for other sites drops away. But not until every scout agrees on the best site and all of them are dancing the directions to this one location does the swarm lift off and travel to that spot to move into their new home.

It’s a fantastic example of truly democratic decision making. The swarming honeybees come to full agreement, and they do it all without a leader. No one has to make do with a decision she doesn’t like. No one restrains herself for the good of the community.

I especially like a few of the honeybee rules:

1. Listen to many voices. In a honeybee swarm, only a small percentage of bees become scouts, but the group is so large that the pool of scouts adds up to hundreds. And each scout’s voice counts; each of them has equal power to bring her perspective.

2. Check everything out for yourself. Each scout reports on her personal experience. No honeybee simply takes another bee’s word. There is no gossip, no hearsay. You don’t speak in the group unless you can speak from experience.

3. No arguing. A honeybee scout definitely tries to recruit others to her point of view by how vigorously she dances, but all she can do is entice another bee to go see a site for herself; she can’t change that bee’s mind. Isn’t that true for humans as well? People are convinced by going to see for themselves, not by hearing others’ opinions.

4. No forcing anyone to agree. Each scout’s point of view gets equal respect. No honeybee pressures another; no one overrules anyone else. Among the bees each individual’s perspective is sovereign, not to be forced or manipulated by others.

5. Use your elders. The scouts, it turns out, are the oldest bees in the colony, bees who spent their lives foraging for pollen and nectar. So they’ve been around. They already know the area well. Using the elders means that the group can collect the largest pool of experience in the shortest amount of time.

![]() I wish I’d learned about the honeybees in fifth grade. I hope kids today are learning about the honeybees, and I hope they’re finding out that honeybee decision making has a few things to teach us about democracy.

I wish I’d learned about the honeybees in fifth grade. I hope kids today are learning about the honeybees, and I hope they’re finding out that honeybee decision making has a few things to teach us about democracy.

I hope kids are learning too to think critically about how our negative view of ourselves infects all our relations, with other humans as well as with other creatures on Earth. I want kids to understand how emphasizing competition in nature has limited what we are able to see about animal and human relations. I want them to know how surviving on Earth means connecting in more loving and respectful ways with our animal and plant kindred, and how connecting means telling better stories of ourselves and better stories of nature.

I hope kids learn to think critically about how this old story that humans are selfish and violent forms the bedrock story, or myth, of capitalism. I hope they learn how it makes this violent system—really just a choice that people made at a certain point in time—seem inevitable.

And I dearly hope that kids learn that an origin story of ruthless savagery in ourselves helps to drive colonialism—that origin stories have consequences, terrible consequences, when they are used to excuse violent power-seeking over others because it’s “only natural.”

And I hope to goodness that kids today learn that we can choose differently. I want them to know that a sense of fairness and justice is built in to animal societies just as it is built into us. I hope they are learning that showing fairness and respect to others, as honeybees do, is also “natural.”

The honeybees give the lie to Robert’s idea that individuals must restrain themselves for the good of the community. The honeybees show a better way than majority vote. And by following a fair and thorough process, the honeybees make life-or-death decisions with remarkable speed.

When Mrs. Rupp called me up to the front in fifth grade to run a meeting, neither of us imagined that I’d be thinking about that afternoon more than fifty years later. And without the nudge from Chris La Tray’s new book, I probably wouldn’t be. So I’ll end with another plug for his book: In a time such as ours when hate-mongers are trying to deny our American history of colonialism, people can promote the truth by learning more about that history. Chris’s book, Becoming Little Shell, tells a piece of the story that many people don’t know, and he tells it with love and care. So, I encourage you: celebrate Indigenous People’s Day every day by learning more American history. And Chris La Tray’s new book is a great way to celebrate!

What other aspects of honeybee life speak to you?

Are there better stories of human nature that give you inspiration? What new stories could we imagine together?

Please leave a comment! Share your imaginings, share your inspirations, or just say hi.

For digging deeper

Check out Chris La Tray, Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home (Milkweed, 2024). Quotes are from p. 132. Buy from Bookshop.org and support your local bookstore!

Anthropologist David Graeber’s new posthumous collection is The Ultimate Hidden Truth of the World . . . : Essays (Macmillan, 2024). The first chapter is available as an excerpt at the publisher’s page. It’s also available at The Anarchist Library under the title “There Never Was a West.” Bow of thanks to poet Devin Kelly in his Ordinary Plots newsletter on September 29 for quoting Graeber and leading me to the book.

Robert’s Rules of Order are in the public domain: Robert’s Rules Online, Revised, Fourth Edition.

Henry M. Robert on submitting to the majority: “The great lesson for democracies to learn is for the majority to give to the minority a full, free opportunity to present their side of the case, and then for the minority, having failed to win a majority to their views, gracefully to submit and to recognize the action as that of the entire organization, and cheerfully to assist in carrying it out, until they can secure its repeal.” From his Parliamentary Law, quoted in Kent Puckett, “B-Sides: Reading, Race, and ‘Robert’s Rules of Order,’” Public Books, April 28, 2023.

Recent critiques of Robert’s Rules:

- From the AAUP, the union of university professors: Afshan Jafar, “Time to Show Robert the Door,” AAUP, October 2024.

- Kent Puckett, chair of English at University of California, Berkeley, places Robert and his rules in the historical context of slavery, racism, and the Civil War: “Reading, Race, and ‘Robert’s Rules of Order,’” Public Books, April 28, 2023.

- A working group on dispute resolution from Harvard Law School and MIT wrote a handbook on building consensus, and the observation that Robert loved order above all comes from there. See Lawrence Susskind and Jeffrey Cruikshank, Breaking Robert’s Rules: The New Way to Run Your Meeting, Build Consensus, and Get Results (Oxford University Press, 2006), and the website of the MIT-Harvard Public Disputes Program, “What’s Wrong with Robert’s Rules?

For more on Afrocentric views of individual and community, see George Sefa Dei, “Afrocentricity: A Cornerstone of Pedagogy,” Anthropology and Education Quarterly 25, no. 1 (March 1994). My introduction to West African thinking came from the Dagara teachers Malidoma and Sobonfu Somé, who said that in their village “community exists to help individuals remember their purpose.” See Episode 15, “Reimagining Community.” Also see Malidoma’s book The Healing Wisdom of Africa (Tarcher, 1999). Full disclosure: I was the development editor for this book.

Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins wrote about what’s implied when a society sets individual and community at odds with each other, as Western thought traditionally does: “The complement of the Western anthropology of self-regarding man has been an equally tenacious notion of society as discipline, culture as coercion. Where self-interest is the nature of the individual, power is the essence of the social.” See Sahlins, “The Sadness of Sweetness: The Native Anthropology of Western Cosmology,” Current Anthropology 37, no. 3 (1996): 404. I agree with Sahlins that Hobbes’s dystopian vision is the “origin myth” of capitalism; he called it unique among human societies. See The Use and Abuse of Biology (University of Michigan Press, 1976), 100.

I traced the evolving story from Augustine to Hobbes, then through Adam Smith and capitalism, and finally to Darwin in chapter 5 of Kissed by a Fox, “Stories We Live By.” I told the story in more depth in an academic version of this chapter, “The Animal Versus the Social: Rethinking Individual and Community in Western Culture,” in The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, edited by Graham Harvey (Routledge, 2013), 191–208. Am happy to send a pdf of the chapter if you request it.

The researcher who has devoted his life to sitting beside beehives and patiently recording their dances and their decision making is Thomas Seeley, and he explains it all in Honeybee Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2010). A short version is “Honey Bee Swarms,” by Thomas Seeley, Kevin Passino, and Kirk Visscher, American Scientist 94, no. 3 (May–June 2006).

Just this week, on Indigenous People’s Day, the story broke that a group of white women extremists in Texas has commandeered their local library’s classification system and changed a children’s book on colonial mistreatment of Wampanoag people from “nonfiction” to “fiction.” See Judd Legum, “Texas County Sidelines Librarians, Reclassifies Book on Abuse of Native Americans as ‘Fiction,’” Popular Information, Oct. 14, 2024.