In eighth-century China all is chaos. The country is at war with itself. Rebels have looted and burned the capital.

“The nation is broken,” writes the Chinese poet Du Fu, “but hills and rivers remain.” I hear the shock in his voice: How can it be, in such a time, that rivers keep flowing and flowers keep blooming and mountains still stand? He can barely see them through his tears.

Broken nations are like that—they break your heart.

Earth remedy

The best remedy I know for a broken heart is to get closer to nature. And the best place to do that is your local area. Your home. This is a time to connect with trees in your neighborhood, to watch the play of light through branches that may now be bare of leaves, to welcome the birds that live with you in winter. This is a time to breathe in the gift of oxygen provided by trees and plants (and plankton), to lean against a tree and feel the scrape of its bark and the strength of its trunk. To ask a tree how to cope, and then to sit and listen for an answer.

This is a time to connect with your local waters—to listen to the gurgle of creeks or the lap-lapping of waves. To lift a glass of water to your lips and say thank-you, hour after hour, with each swallow. To feel, in the shower, the gift of water on skin and to allow tight shoulders to relax. To sit next to water and to ask water how to keep flowing strong and free in a time like this.

This is the time to sit with a rock. To appreciate that it has been in this form longer than anything else you can see. To imagine its eons-long life, from the hot stew of minerals underground through its unbelievably long journey to the surface, to the eons-of-eons of waters and winds and fires that shaped it and broke it and rounded it and sharpened it. This is a time to borrow some stillness from rocks.

Or, just orient yourself within the four directions and breathe. My friend Susan Tweit offers this lovely meditation for rooting yourself in your home place.

Receiving the gifts of air, water, light takes little effort. These are sure remedies for broken hearts.

Because hills and rivers need our care

But there is another part to the healing process, and it happens when we join in caring for these same trees or waters, when we give a little effort, maybe some sweat, to the land that holds us close.

Because hills and rivers remain, and if they are going to continue to nourish and heal us, they need something from us in return. They need our care.

And as the new regime in Washington has promised to do away with protections for nature, it appears that local areas will need to look out for their own Earth. So this is an opportune time—the best possible time—to dig even more firmly into your home land, to deepen your commitment to caring for your local Earth.

Waiohuli Kai Wetland

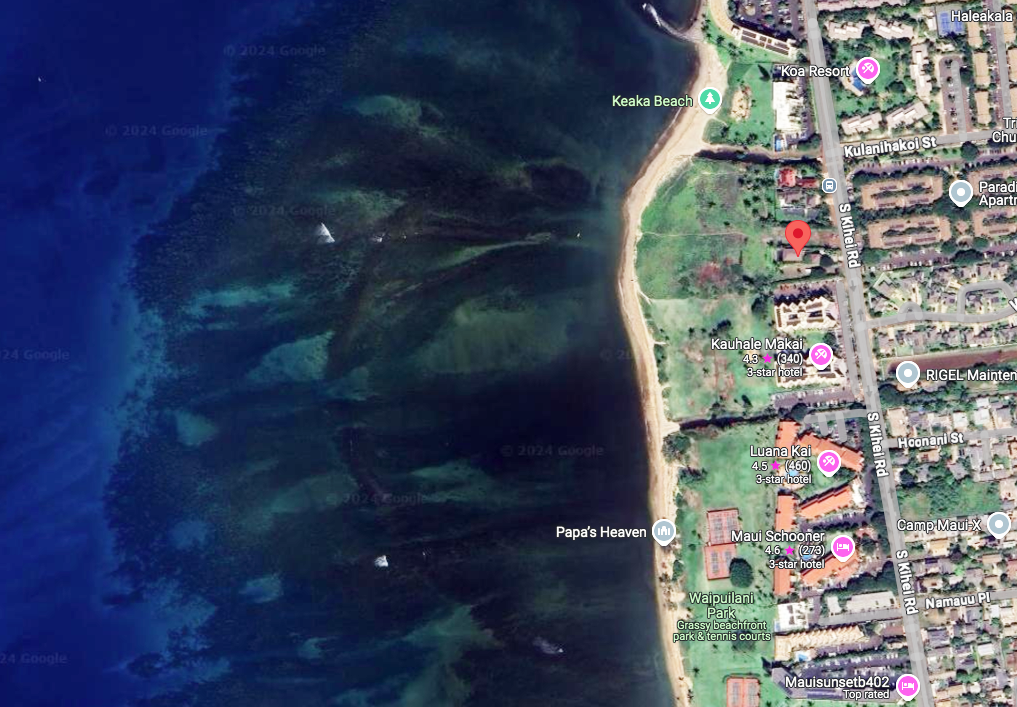

I had the privilege of doing this recently on a restoration project taking place right here at home in Kihei. The Waiohuli Kai Wetland is a spring-fed stretch of low land lying next to the ocean. Back in the seventies, as resorts took over the shoreline, the wetland got trashed. Low-lying areas were filled in. Golf course grass crept across the ground and choked out native plants. The lagoons that had dotted the surface, providing homes for birds and places for stormwater to flow, dried up. The canal running through the area ran stinky and brown.

Then a local man, Cody Nemet, called “Koko,” took an interest. He’s third from right in the photo below.

Koko had grown up visiting this area with his parents, picnicking on the beach, swimming in the waters, diving among the reefs. He knew the history of the place—that a large Hawaiian fishpond lay right offshore. That the lagoons dotting these lowlands used to be outlined thick with native grasses and trees, with birds flitting everywhere. That many heiau (temples) used to line this beach for offering the first catch of the fish in thanksgiving for their abundance.

When all the oceanside parcels had been snapped up and only one was left free, the county of Maui acquired it to preserve it for stormwater runoff. Koko and his buddies began dreaming.

And then they got to work.

Patient and slow

The new caretakers noticed native plants popping up here and there, and they decided to work with the existing plants, just encouraging them where they live instead of making sweeping changes. No mass clearing out of invasives. No transplanting native plants because “You know how hard it is to transplant native plants?” Koko says. “You have to use sterile conditions, and then often the plants don’t like where you put them.” So they decided to simply make room around existing plants, knowing that if the plants can breathe, they will expand, slowly filling in the land.

Over time they watched native plants spread after being shown the slightest bit of love. And they saw new natives pop up randomly. The caretakers had their suspicions confirmed: there is a robust native seed bank in the ground just waiting to sprout again.

Restoring land only by clearing around existing natives is slow, patient work—so slow you can barely see any results from month to month or even year to year.

But after four or five years the results are luscious. The old stinky canal now runs fresh and clear, lined with native grasses and plants, as you can see from the photo at the top. It is merely the first of many tropical lagoons that I’m sure will emerge again on this land. And after healing just this one small stretch of lowland, the birds have returned, and neighbors say they can hear the pueo, the Hawaiian short-eared owl, calling in the evenings.

Caring for family

Koko explains at the start how the morning will go.

“We’re going to be weeding, but this isn’t about going in there and ripping things out. We’re going nice and slow,” he says. “This is about getting to know our native plants and what they like.” He goes on, “You know that word kamaʻāina?”

It’s what those of us who live here are called, if we’re not Hawaiian, and it’s the name of the local discount we can sometimes get, the kamaʻāina price.

“Kamaʻāina means more than just a sale price,” Koko goes on. “ ‘Āina means land. Kamaʻāina means a person of the land. It means familiarity. Being familiar with who lives here. We’re going to take time just to get familiar with our native plants here.

“To us as Indigenous people, these plants are family,” he goes on. “When we give them room to grow, we are caring for our family.” Mālama ʻāina, caring for the land. “When you’re little, who feeds you?” he asks. “Your family. This land feeds us. We care for the land, mālama ‘āina, so the land can feed us. This land is our family.”

ʻUhaloa

We walk out to the wetland. Koko explains the different work zones in the wetland.

He leads us to today’s work zone, an area covered by a thick mat of golf course grass, dry and brown. Here and there other plants poke up out of the dense cover. He introduces us to ‘uhaloa, who will be our focus today.

I recognize this plant from disturbed soils near my house. ‘Uhaloa moves right in, even after a place has been blanketed with pesticides, and grows as if there’s no tomorrow.

Up until today I thought of ‘uhaloa as weedy, unattractive, as many pioneer plants are. They’re trying to spread fast and heal the bare earth, after all.

But today I learn that ‘uhaloa is full of medicine. The Kānaka Maoli (Hawaiians) use the flowers, roots, or leaves for many kinds of ailments: asthma, sore throat, arthritis, fatigue, and more.

Our job today will be just to take care of this plant, to mālama ‘uhaloa. “Take your time,” Koko repeats. “Get to know this plant. Feel the dirt. Notice what kind of soil it is.” When we have spent time sitting with a plant and getting familiar, we can start digging and pulling up grass around it. “Just make it nice and neat around the plant so it has room to expand,” he says.

While we work, Koko keeps talking. He has the patient, steady voice of an educator who has been explaining this work since forever. In fact, he does it several days a week—orienting classes of schoolchildren who visit the wetland to learn about their culture and training groups of volunteers armed with weeders and trowels. I’m here today because the Maui Nui Marine Resource Council agreed to send a crew.

In my corner of the project we are mostly quiet, each of us bent to our own ‘uhaloa. We are sweating, digging beneath the mat of grass, tugging hard at underground runners. It takes a while for us to start talking. But, as always happens, with our hands in dirt we eventually start chatting, and soon we are talking story, comparing notes. By the end of the morning we know where everyone lives and which birds they listen to in their neighborhoods.

And by the end of the morning dozens of ‘uhaloa plants have more room to breathe.

Gentled by the Earth

Putting our hands in the earth this way gentles us, the way frightened wild horses can be gentled by calm, soothing touch. This is the medicine of the Earth—to soothe our choppy minds when we take time to connect.

But the medicine of dirt might soothe our social relationships as well. Because for all the heartbreaking results of this election, one positive result—one incredibly hopeful and to me unexpected result—is that across the country, people voted for the environment. Amanda Royal detailed it in a post-election post—how people in red states as well as blue voted for conservation, for climate mitigation, for coastal and forest restoration, for clean drinking water.

Enjoying a livable Earth is one place where people might be able to meet across political or religious differences. Local conservation projects—cleaning beaches or creeks, protecting local parks, planting pocket prairies in your neighborhood or pocket forests, or doing trail maintenance—are precious places to meet neighbors and share your commitment to caring for your shared home. I learned this long ago during my first creek cleanup.

And working for the Earth, especially when people do it with others, can change hearts. Knowing you love the same place on Earth can soften the edges between people. And spending time together outdoors, taking care of the Earth together, can build goodwill between people who might think they have little in common otherwise.

The nation may be broken, but mountains and rivers remain. And they have power, when we love them, to build ties of love between us as well.

Spring View

by Du Fu, translated by Arthur Sze

The nation is broken, but hills and rivers remain.

Spring is in the city, grasses and trees are thick.

Touched by the hard times, flowers shed tears.

Grieved by separations, birds are startled in their hearts.

The beacon fires burned for three consecutive months.

A letter from home would be worth ten thousand pieces of gold.

As I scratch my white head, the hairs become fewer:

so scarce that I try in vain to fasten them with a pin.

Do you have a favorite spot to sit in nature, a place to collect yourself?

Have you taken part in restoration work? What did you learn? How did it go?

Let us know in the comments! And if you got this far, as we say in Hawaiʻi, mahalo!

thanks for an inspiring story.

Mahalo, Kathy, glad you connect. I find their work super inspiring—the commitment to long-term caring for this wetland. I sat around afterward to chat with Koko a bit and learned about their plans for 20, 30, 40 years down the road. They can plan like this because they belong. They will be here because this land is family. I learned a big lesson about Indigenous belonging, and how each place that people live can be cared for in this way, by people who regard their home place as family—and they’re committed to family for the long haul.

Yes, a good lesson for us all as we approach a seemingly destructive administration when it comes to our environment.

Yes, and even though local areas may be on their own to protect water and air and land, there is already momentum in many places that can be used and built on. I also take big inspiration from the fact that the clean energy revolution is going forward with or without him, because economics. https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2024/11/hell-try-but-trump-cant-stop-the-clean-energy-revolution/