Transcript

I’ve been thinking about animals recently. Actually, I do that a lot. I enjoy the company of animals, and I feel more alive, more myself, when I can hang out with them. So for decades I lived with a dog or a cat or both, and on top of that I connect with animals as regular mental health and spiritual practices. Walking a dog and listening to birds or hiking in a forest or rehabbing wildlife—I’ve done all of it a lot. And now that we live in Hawaiʻi we’re getting to know the fish and wildlife of our local reef, and I’m keeping a life list—more than 150 species so far, and we’ve barely started on the limu, the seaweed.

And from all the thousands of hours I’ve spent around animals, one thing stands out: Animals live to live. They are dedicated to surviving.

I wish the same could be said of us, but I have my doubts. Let me explain with a story.

We all know how fierce mother bears can be in protecting their young, but some years ago I learned that even deer, who look so shy and sweet and quiet, can get murderous on behalf of their children.

We were living in Boulder, Colorado, and a doe gave birth to twin fawns somewhere in the dark corners of our backyard. We’d just gotten a new puppy, and he hated anything that moved on the property. So we soon learned to keep the back door shut so he wouldn’t see the deer. But one June afternoon the warm sun was just too inviting, and I’d left the door open to enjoy it.

And just then, Mama Doe drifted into the yard, browsing in the grass. Her fawns were out of sight. But through the screen door our puppy saw the doe and rocketed into high gear, barking and snarling. The doe lifted her head and stared at the door. She took one step toward the house, then another. Then she was striding, fast, toward the porch. By the time I reached the door, she already had one hoof up on the tiny porch and was heading straight for the screen. As I slammed the door shut I saw murder in her eyes.

I hope I never see such focused intent on an animal’s face again, ever—at least not when she’s heading straight toward me. It wasn’t exactly fury; it was a blazing intent to rid the world of this danger to her little ones. And she would have too. Deer have sharp hooves, and they can and do trample dogs that threaten their babies.

That mother doe didn’t dawdle or delay. She didn’t hesitate. She just did what had to be done in the moment to protect her children.

That mother doe didn’t dawdle or delay. She didn’t hesitate. She just did what had to be done in the moment to protect her children.

In the face of big dangers, like a pandemic and climate change, we human beings are not doing the same. We are failing in spectacular ways to protect our children.

So, let’s talk for a minute about the pandemic.

Back in 2020, at the start, we heard a lot of things about COVID and children. Things like, “It’s not as severe in children.” Or “Children are not likely to die from it.”

And most of us breathed a huge sigh of relief. At least the kids would be all right.

But those messages turned out to be only partly true. They were hopeful messages that everyone wanted to believe, but they were messages that minimized some of the real dangers of COVID. But those messages kept getting repeated, even after it became clear they weren’t the whole truth.

And eventually these minimizing messages won out at every level of society, from local school boards to the top decision makers at the CDC. We’ve abandoned, one by one, every effort to slow or stop the spread of the disease—for children as well as adults. We still have vaccines, which do decrease the severity, but they do not stop the virus from spreading. We’re essentially practicing a “let ’er rip” policy, and children are completely vulnerable. We’ve left the kids unprotected.

And we’re doing it because of minimizing. And minimizing is a form of denial.

Denial is deadly. When we’re in denial, we’re determined for the world to be other than it is. And people who are in denial often fail to take care of themselves. They aren’t fully committed to surviving.

So right now, many children are getting sick. And it makes sense when you realize that almost all children and adolescents have already caught COVID at least once, and some more than once. And when you factor in also that after even a mild case of COVID, every child (as well as every adult) is at greater risk for other serious conditions, such as heart or kidney or lung failure or diabetes, it all adds up to a nightmare of a health crisis.

The kids are not all right, after all. And it hurts my heart. We are failing to protect the children—something so basic that all other mammals can do it without even thinking about it.

And maybe that’s exactly the point. When a mother doe attacks to protect her young, she is not thinking about it. Not a hair of daylight exists between her mind and body. She acts in perfect harmony with what needs to be done to survive.

But we humans have this magnificent forebrain, which allows us to reason and think about the world. And our thinking brain is so powerful that it can direct us right away from physical realities. Humans are able to live in denial. I’m not sure any other animals can.

The irony is that for centuries in Western culture, we’ve considered ourselves so vastly superior to the other animals because of our reasoning power. Yet we’ve never really grasped that it may be our reasoning power itself that can direct us away from surviving. We may be the only animals who can live in denial.

The cure for denial is waking up to reality. It means dropping our defenses against what-is. Many people go to therapy to wake up. Therapy often involves facing difficult life experiences and feeling our most uncomfortable feelings about them. Being willing to feel brings us to the truth of who we are.

Connecting with nature is another path to waking up. It is hard to be in denial if you practice being present with nature. Going forest bathing to soak up the goodness of trees or sitting beside a stream or a lake or an ocean or listening to our own body, which is our own solid presence in nature—each of these, if we do them on a regular basis, will bring us face-to-face with what cannot be denied. With the reality of a physical world whose mysteries we cannot fathom and whose power is beyond our reckoning.

And here we come to what may be the crux of denial: the fear that we feel in the face of a nature that we don’t understand and can’t control. A virus is another actor in nature—powerful and changeable—so we are vulnerable in its presence. And then we are tempted to leap to arrogance to mask this terrible awareness of just how precarious our lives really are. Fear and arrogance—it’s a toxic brew that propels us straight toward denial, toward erecting walls against knowing our vulnerability.

To live is to be vulnerable—to illness and accidents and dying. And when we are all tied up in denying the truth of how precarious life is, we cannot feel compassion either for ourselves or others. Compassion requires the truth. Being truthful—about our fears, about our vulnerability—allows us to relax into compassion. To crawl out of the bunker of denial is allow the heart to grow. To touch reality is to emerge into largeness of spirit.

I think of being truthful as becoming more like animals. Living from the power of a mind and body joined, with no separation. Acting with singleness of purpose, no minimizing, no dithering. It is how other animals live—looking out for their survival, taking care of themselves and their families and communities without a second thought. Seeing reality clearly and acting in accord with it. No denial.

I recently discovered that none other than Carl Jung shared this perspective. A hundred years ago he recommended what he called “living your animal.” It’s a rich phrase, and I wondered what he meant, so I delved into it further.

When he was around forty, Jung went through a several-year process of opening to the images or visions that arose in his mind in the evenings during his off-work hours, and he wrote them down in what became titled The Red Book. In one section of The Red Book he wrote about how animals are “well-behaved” and “just.” He recommended that we human beings learn from animals how to treat others fairly. “There is not one [animal],” he wrote,

that conceals its overabundance of prey and lets its brother starve as a result. There is not one that tries to enforce its will on those of its own kind. Not a one mistakenly imagines that it is an elephant when it is a mosquito. The animal lives fittingly and true to the life of its species, neither exceeding nor falling short of it.

For Jung, to learn to live “fittingly and true” in this way was to “live your animal.” And it is crucial to live your animal, he said, because if you don’t, you will not treat other human beings well. “[Humble] yourself,” he wrote, “and live your animal so that you will be able to treat your brother correctly.”

Many people today think that acting “like an animal” means following raw physical urges for food or sex, or that it means acting wild and crazy. There is a long story in Western history, stretching back 2500 years to Plato and Aristotle, that animals lack reason and that they act only out of passion. In modern science it morphed into the idea that animals act out of “instinct,” with instinct being defined as something different from feeling or comprehending. So we’ve been denying reason and understanding to animals for a very long time.

But Jung took issue with this view. In a seminar that he taught in 1930 when he was in his fifties, he said,

People . . . think the animal is always jumping over walls and raising hell all over town. Yet in nature the animal is a well-behaved citizen. It is pious, it follows the path with great regularity, it does nothing extravagant. . . . So if you assimilate the nature of the animal you become a . . . law-abiding citizen, you go very slowly, and you become very reasonable in your ways. . . . For it is very difficult to be reasonable; you are quite different from what you assume the animal to be.

I like that view. Jung saw that animals abide by the laws of their kind; they don’t forget their own. Living your animal does not mean acting wild and crazy; it means rather the opposite: Treating others fairly. Sharing your goods with others. Caring for your family and community.

And in fact, these are the traits that more recent animal scientists find when they observe animal behavior. They discover among animals a sense of fairness and justice, an urge to cooperate. I think of what animal scientists Marc Bekoff and Jessica Pierce wrote on the very first page of their book, Wild Justice: “Let’s get right to the point,” they wrote.

In Wild Justice, we argue that animals feel empathy for each other, treat one another fairly, cooperate towards common goals, and help each other out of trouble. We argue, in short, that animals have morality.

Bekoff and Pierce are not the only ones revising the old story. Other animal scientists find that animals are so fair-minded that they may feel distressed or even angry if they get a treat that their companion doesn’t get. When it comes to fairness and justice and seeing reality clearly, we have some big things to learn from animals.

And my background in religious studies shows me much the same thing. I’ve engaged in a number of spiritual practices over the years, and each one of them is trying help people remember how to be whole. How to stitch body and mind into unity again so that we can treat one another with more fairness and more compassion.

For instance, yoga. The word yoga is Sanskrit for “yolk,” and the practice of yoga is designed to yolk together body and mind—to bring us into a cohesive whole so that we can act from a pure and ready heart, a heart that is fully aware and in touch with reality. Or I think of Zen Buddhism, with its breathing meditations and its koans designed to help people get out of their thinking minds and into something more elemental—a way of being that is more direct, more in harmony with how things really are.

Neither yoga nor Zen, as far as I know, takes their model consciously from animals, but from all I know about animals, this unity of mind and body is exactly where other animals dwell from the start—and it’s what we humans have to practice, through meditation and therapy and spiritual disciplines, to remember. From what I can see, the goal of many religious traditions is to help people remember to “live their animal.”

In the spiritual practice I now engage in and teach, we make this very explicit. The practice is one of going on meditative journeys with animals as interpreters of Spirit. (We call them “spirit journeys” or “shamanic journeys.”) The process of the journey is very close to what Jung himself practiced in what he called “active imagination.” It’s a process of becoming quiet and then allowing images to arise in the mind. And then instead of trying to direct or control the images, we just watch them and open to them and see what can be learned from them. I might frame the practice a bit differently than Jung did, but the actual moment-to-moment experience in a journey is very similar to how he described active imagination.

It may be no accident that spirit journeys have a close kinship with Jung, and that when we engage in spirit journeys we come out at a similar place as Jung did: closer to a unity of body, mind, and spirit. Closer to “living our animal.” If you’re curious about how this process worked for me—and how it worked on me, during the first year—you can check out my book Tamed by a Bear.

So we have a great deal to learn from animals about how to live closer to reality, or as we often say, closer to nature. And with regard to COVID, we need a lot more of “living our animal.” We need being truthful about a deadly pathogen still circulating among us, instead of trying to minimize it or ignore it. Because only by seeing it clearly can we take steps to stop it from spreading. And only by stopping the spread can we all be safe. For in a pandemic, we’re not safe until all of us are safe.

In the very hour that I am writing these paragraphs, the journal Nature publishes a new study: a consensus study that brought together 386 health experts from 112 different countries. They came to agreement on what needs to happen at this point in time with regard to COVID. Most of their recommendations come in at close to or more than 90 percent agreement from all 386 people. And these near-unanimous recommendations include things like:

- Making tests and protective gear and treatments economically available to all;

- Preventing the spread of COVID through multiple paths, like wearing masks, working remotely, installing air-cleaning equipment;

- And of course, giving much more attention to protecting the children.

I see a lot of truth telling here. These 386 health experts are seeing reality clearly—not shying away from the things that need to be done to take care of ourselves. Most of the actually pathways toward safety are easy: face masks, air filtering, safety equipment. The much harder part is bringing our minds into alignment with our bodies: leaving behind denial.

We need more fierceness on our own behalf, and on behalf of our children. We need more single-minded purpose—the kind of energy that gets freed up when we drop our defenses and denial and come out of our bunkers to face the truth.

And the truth is that life is precarious, and we need to do everything we know how to do to survive.

And the truth also is that life is so very, very precious that it’s worth every effort.

Wishing us all the fierce, clear sight of a mother doe protecting her fawns: the courage to step out of denial, the heart attuned to reality, and the power to act from a mind and body joined as one.

For digging deeper

The studies showing dangers of even a mild COVID infection are legion. A study published in June analyzed dozens of other studies to show that a quarter of children infected with COVID developed lingering symptoms of Long COVID. See “Long-COVID in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” by Sandra Lopez-Leon et al., Scientific Reports, June 23, 2022.

For the risk of heart problems in adults after COVID, see Mariana Lenharo, “Even Mild Covid Can Increase the Risk of Heart Problems,” Scientific American, March 2022. For the risk to children of heart, kidney, lung or diabetes problems after COVID, see Lyudmyla Kompaniyets et al., “Post–COVID-19 Symptoms and Conditions Among Children and Adolescents—United States, March 1, 2020–January 31, 2022,” CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Aug. 5, 2022.

Already back in April the CDC estimated that 75 percent of children and adolescents had caught COVID; see Melissa Jenco, “CDC: 75% of Children, Adolescents Have Had COVID-19,” American Academy of Pediatrics News, April 26, 2022.

The visions and images that Jung recorded over several years in The Red Book are fascinating and were published only in 2009 (edited by Sonu Shamdasani, published by Norton). A free online reader’s edition is available, without the illustrations Jung painted, at D-PDF.com. The transcript of Jung’s 1930 seminar and his words about animals are found in Carl G. Jung, Visions: Notes of the Seminar Given in 1930–1934 (Princeton University Press, 1997), 2:699. Jung wrote about active imagination in Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Random House, 1961). Wikipedia has a good introduction to active imagination.

For a real-life example of how spirit journeys or shamanic journeys can make a difference in everyday life, see my book Tamed by a Bear (Counterpoint, 2017).

Any of Marc Bekoff’s dozens of books on animal behavior is a treat; the quote comes from his book cowritten with animal ethicist Jessica Pierce, Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals (University of Chicago Press, 2009), 1. Other scientists who write compelling books about animal behavior include Frans de Waal, Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? (Norton, 2016), and Carl Safina, Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel (Macmillan, 2016).

The worldwide consensus study about how to address COVID right now is authored by Jeffery Lazarus, et al., “A Multinational Delphi Consensus to End the COVID-19 Public Health Threat,” Nature, Nov. 3, 2022.

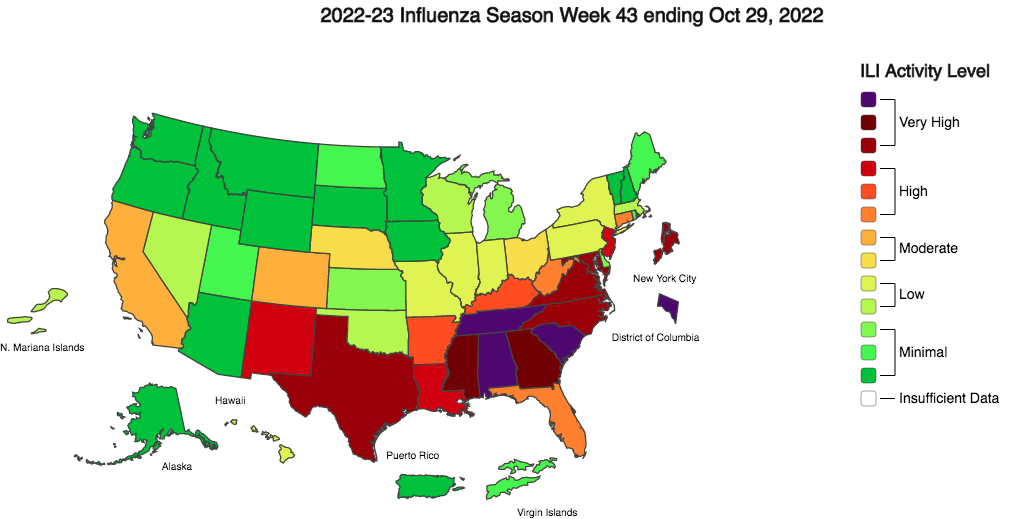

And in case anyone is wondering, “immunity debt” is not a thing, medically speaking. The idea of an “immunity gap” was made up in 2021 by a group of French doctors using mathematical models, not medical evidence. Immunity debt is the idea that COVID mitigations, like masks or school closures, prevented children from catching bugs earlier in life, so now they’re catching them more severely. This is nonsense! Our immune systems don’t get weakened from not catching bugs, they get weakened after catching them. If the immunity debt were true, then states that practiced more mitigations should see more sickness now, and states with fewer mitigations should be healthier now. It’s not working out that way. Go to the CDC’s “Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report,” and scroll down to the map titled “2022–23 Influenza Season Week 43,” shown here. Many of the states that did little to limit COVID are getting hit hardest now with the flu.

Meanwhile, the evidence that COVID damages immune systems continues to grow. A Twitter user named Andrew Ewing collected 25 studies and articles that show post-COVID immune deficiency. You can read it at the Thread Reader App (as long as Twitter exists). Full link here for accessibility: https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1588306678814056449.html

I love the way you mix practicality, reading, spirituality, and nature . . . the way life itself does!

Thanks, Judith! They say write what you know, right? 🙂 So many people think of spirituality as otherworldly, and look where that has gotten us! So, showing how spirit, nature, animals, humans are all related, all making it up together, might help. At least I hope so!

Priscilla, you’ve raised so many interesting points, but I would like to discuss just one of them. You make the point that animals cooperate with each other, but I’ve seen instances of animals sacrificing one of their own for the greater good of the community. At my cabin in the mountains, I see a flock of wild turkeys every day in winter. Last winter, the turkeys shunned one turkey who had a disfigured face. In doing so, the disfigured turkey was isolated and was killed by a bobcat. In this shunning, it looks like the other turkeys knew the disfigured one wouldn’t survive anyway, so were willing to give her up to the bobcat, so the others could be saved. It appears the community, not the individual, is more important.

That’s a great question, Kathy! In Wild Justice, Bekoff and Pierce devote a whole chapter to “Cooperation: Reciprocating Rats and Back-Scratching Baboons,” with tons of examples documented by many animal researchers. But our human-language terms and categories can be slippery or even misleading. Maybe what you saw among turkeys was about disability rather than cooperation? And maybe turkeys follow different “species rules” than, say, elephants? Bekoff & Pierce, on pp. 6–7, cite the work of elephant researcher Joyce Poole, who watched a family of African elephants protect a teenager among them who had a disabled leg when this teenager was attacked by a young male. And maybe even turkeys change their “rules” depending on the season (mating or not) or on how abundant food is at the moment? Emphasizing how animals cooperate does not negate the fact that some species reject or kill some of their offspring depending on “species rules” or abundance. What emphasizing animal cooperation does do is remind us that the picture of animal behavior is a lot more complicated than the old “red in tooth and claw” picture we were all fed until very recently. I’m curious about your wild turkeys: why would they do what they did? It’s a question worth pursuing.

The more I observe wildlife, the more surprised and impressed I am. We’re still learning, that’s for sure.

So true! Because in Western history we only started observing animals so recently, like around Darwin’s time. Before that, it was philosophical dogma about what animals are or what they represent. For instance, Hobbes and his idea that animals have no social rules—a longstanding dogma by his time already in the 1600s. I’ve been reading Pliny from Roman times, who collected all the knowledge about all plants and animals known in the first century. What he “reported” about bears, for instance, was complete hogwash—because it was based not on observing but rather on what the philosophical authorities before him had written. It was the received wisdom dating back to Aristotle. And when Western scientists DID start observing animals in the nineteenth century, it was from this framework of negative attitudes toward animals—that they’re just trying to destroy one another, or that they just compete with one another. I’m so glad more recent scientists are seeing more nuance.