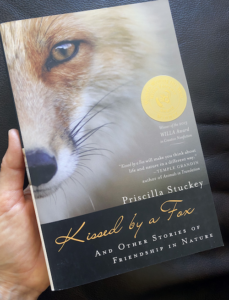

Welcome to “Kissed by a Fox: Short Takes,” where we celebrate my first book by looking at snippets of the book from the perspective of a few years down the road. I’m thrilled to say that the book is still finding new readers, and deep thanks if you’re one of them! All block quotes in this post are taken from the book.

Every so often I get an email from someone teaching at a university who just read Kissed by a Fox. They are brimming with gratitude that I write about things they too may have experienced but feel they can’t talk about at work. “I have a special tree,” they might say, “and I go and sit there when I need to hear from the trees.” Or they might tell about a deep experience they had one day meeting a river or a mountain and then add, “That day changed my life.”

But usually they come around to this: “I’m not comfortable talking about these things in my department. I could lose my job.”

Running on Separate Tracks

I know what they mean. There’s a taboo in the academy on straying outside Western rational ways of knowing. I lived by it for years. As a doctoral student I never considered writing about the experiences that became the heart of the book—a visitation from a tree, a meeting with an eagle—even though those experiences were happening at the very same time.

Heck, I never even considered mentioning those experiences, not even to my peers, let alone to teachers.

I was not in a science program, where nonrational ways of knowing clearly lay outside the bounds of the scientific method. I was in a theological school where it was normal, even expected, for people to pray or meditate or believe in God.

Yet even there, as in all the humanities, we followed a scientific method of inquiry. We confined our writing and our talk to the rational and the empirical, never allowing personal faith to interfere with the pursuit of knowledge. No one ever disclosed anything visionary we might have experienced, especially if it didn’t fit into the traditional paths of spirituality laid out by our churches or temples or sanghas. Anyone who admitted to talking with trees was likely to get labeled as “new age” or maybe just “crazy.”

Which is why it took me so long to bring these two parts of myself together: spiritual and intellectual. And why, when people assume Kissed by a Fox is based on my doctoral research, I have to say unfortunately no.

During grad school I was operating on two separate tracks that never, ever met.

Asters and Goldenrod

Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi) tells a story in Braiding Sweetgrass (in the “Asters and Goldenrod” chapter) of entering college as a young Indigenous woman. She had already spent years knowing and loving and interacting with plants, but she was eager to learn more. When a faculty adviser asked during an intake interview why she wanted to study botany, she offered him her most profound question: “Why do asters and goldenrod look so beautiful together?”

The professor was unimpressed. “Miss Wall,” he responded, “I must tell you that that is not science. That is not at all the sort of thing with which botanists concern themselves.”

The botany she went on to learn in the academy, she writes, “was reductionistic, mechanistic, and strictly objective.” It was not interested in beauty, or in love. Her college education led her to doubt what she had learned in all the years before. She could only conclude “that the things I had always believed about plants must not be true after all.”

What a tragic stifling of a brilliant young voice! It would take her many years to find her way back to her Indigenous worldview, back to what the plants themselves had taught her, back to trusting the knowledge that grows out of heartfelt relating with plants and people and Earth.

Challenging Western Knowing

In Kissed by a Fox I was telling stories of nature experiences that directly challenge Western definitions of knowledge. My stories strayed not only into the domains of love and beauty but also into things that might happen when the heart is open and the mind is seeking—unique experiences, even extraordinary ones. Because all kinds of interactions from the mundane to the wondrous become possible when you expect the other, whether tree or creek or fox, to be a “who” not an “it.”

So I needed to spend some time in the book addressing the issue of knowing. Why is it taboo in the academy to discuss those special times when nature slips back the curtain and shows us something wondrous? Why must scientists never gush about how they love the land?

Why is talking about the animate world Not Safe For Work in higher ed?

Superstition

In chapter 11, I tackled the issue of superstition, for superstition was the big bugaboo during the scientific revolution—the issue it all came down to in the struggle to define knowledge during the Enlightenment. The new scientific elites were determined to break the power of the medieval Catholic church and banish every piece of the magical thinking they associated with it.

Listen to how Francis Bacon derided the idea of a living world:

Leaders of the Age of Reason in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were determined to drive out all remnants of [an] earlier irrationality—leftover medieval rituals and spells, all magical practices that could not be explained by the new science. The English philosopher Francis Bacon wrote in a book published in 1627 about the awful superstitions and “monstrous imagination” linked to the ancient idea that the world is alive. Those archaic misguided folk believed that “if the world were a living creature, it had a soul and spirit.” One can just about see his hands raised in horror. Such thinking opened the door to all sorts of irrational and unrestrained magic. “With these vast and bottomless follies,” he clucked, “men have been in part entertained.”

They were fighting an ideological war over who gets to define what counts as knowledge.

To us in hindsight, their intellectual choices look political more than purely rational; they were struggling to break the power of the medieval Church and install in its stead a new, scientific, elite. And they were trying as well to stamp out livelier, animistic views of nature in their own towns and villages. . . .

Reduced to Feather or Bone

I have to say that in one limited way I am in sympathy with those Enlightenment scientists. This is something I didn’t talk about in Kissed by a Fox: that though I experience the Earth and every part of it as alive and speaking, I too am discontent with the native European form of animism. I don’t draw on it for knowledge of the Earth or for inspiration in shaping contemporary animism, including my own spiritual practice.

Yes, those medieval villagers may have seen a soul or spirit in the living world, as Bacon scoffed. But to me their spirituality also has a utilitarian quality, a willingness to use the others of the Earth as means to human ends.

Much of European folk religion appears in the written documents in the form of lists and recipes—ingredients that a practitioner would need to gather and stir into a potion or salve in order to solve a problem or cure a disease. For example, one medieval Latin recipe called for rubbing the heart of a lark on a patient’s stomach to treat abdominal pain.

Many of the medieval recipes were remedies, in other words. Medical prescriptions. And like prescriptions, they were intended to exert power—to make illness go away.

The ingredients came from animals or plants, but the documents show no curiosity about the beings who provided them. The giver of the ingredient was reduced to one single element, to the root or bone or feather taken from them—often at the price of their life—to serve an unrelated human purpose.

As if people could extract the parts of a creature they found useful and leave the rest.

A Collection of Parts

Western minds have a tendency to see nature as a collection of parts, writes John Fowler in his little gem of a book, The Tree (1979). (Fowler is best known for writing The French Lieutentant’s Woman.)

Ever since Aristotle, he says, people in the Greco-Roman tradition are preoccupied with classifying things, giving names to the parts of nature and interacting with them one by one—so much so that we have trouble seeing their interconnections. We “treat the flight of the bird and the branch it flies from, the leaf in the wind and its shadow on the ground, as separate events,” he says.

We tend to overlook the “togetherness of beings,” Fowler says, and he calls it “a strange cultural blindness.” It “seriously distorts and limits any worthwhile relationship,” he adds.

It predisposes Western people to treat the others of nature as things rather than to relate to them as companions in a shared community.

Magical Tradition

This strange cultural blindness shows up in those lists of ingredients from medieval medicine and spirituality. The European folk animism was a spirituality of assembling charms and working spells to make something happen in the world. It was a magical tradition. And Europe had inherited it from the Roman Empire.

So here is one small piece of my doctoral program that did make it into Kissed by a Fox, into chapter 11: a bit about Roman religion. In the Roman world, people practiced a spirituality of magic. Magic was the religion of the everyday.

Millions of people throughout the empire repeated omens and performed magical spells to manage all the out-of-control events in their lives, from unfaithful lovers to intractable illnesses to misfortunes of every hue. Their spells passed down through European history and became the tokens of animism that the elite were determined to wipe out at the dawn of the scientific revolution.

The tradition of omens and spells and recipes continued strong in European life throughout medieval and Renaissance times, and church officials often railed against it. But folk traditions persist, and people handed them down for generations, even into the present. When I was a child I heard rumors of a secret tradition of healing, with charms and spells, that circulated among the older generations of my family. Scholars believe the recipes in this tradition go back to pre-Enlightenment times.

Inflected by Empire

And it’s that utilitarian quality of the European magic that has always left me uneasy. Taking parts of animals or plants and using them to change one’s fortune—to cure an illness or bring a lover or ensure prosperity—has more to do with exerting power over the forces of nature than it has to do with being curious about the other creatures or seeking to live in harmony with them.

That emphasis on power makes sense if we consider that the spirituality of medieval Europe came from a Roman world that resembled the later European one in striking ways: a small set of landowning families controlling the resources of the Earth while masses of people worked the land, nearly starving. A religion that set its eyes on heaven (something that was true of many of the Roman religions prior to the Catholic Church). A far-off emperor who forced men to fight and die for his political interests.

Practicing a spirituality that offers some control over the events of daily life makes sense when people have so little real agency. The Roman magic had been shaped by empire, and it passed into a feudal Europe where power was organized in similar ways.

European animism, like the Roman forms before it, was inflected by empire. It served imperial aims of controlling nature more than understanding it or participating in it.

And this mindset of control, no stranger to European history, intensified during the time of the Enlightenment philosophers.

Power over Nature

The early scientists wanted power over nature, and they did not hesitate to say so. They intended to erase uncertainty from human life by shaping nature to human will:

The scientific revolution was used to strip the animals and plants of subjectivity, to turn them into objects ready for human use. For, as Francis Bacon put it in 1620, “Knowledge and human Power are synonymous,” and the purpose of knowledge is to further “the empire of Man over Things.”

Bacon thought that setting out “to renew and enlarge the power and empire of mankind in general over the universe” was a purpose far more noble than merely wanting power for oneself, which was only corrupt. But to control the universe on behalf of all humanity? Now that was a truly worthy ambition.

The problem with medieval superstition was that it wasn’t accurate enough to offer true power!

Isaac Newton, born twenty years after Bacon’s writing, went on to discover perfect predictability in the heavens, and the philosophers who followed him were certain that all of nature’s mysteries could be calculated—and thus controlled—through these mechanistic laws.

Power over Others

But power over land and animals and plants was not enough. The Enlightenment thinkers also wanted power over other human beings:

For it must never be forgotten that the scientific revolution took place alongside the voyages of conquistadors and colonists and slave traders and was sometimes directly financed by them. Mastering nature went hand in hand with mastering other people.

When I was writing the book, I had to dig deep to find research on the connections between early scientists and the slave trade, but today those sources are plentiful. Carolyn Roberts is one historian who shows how thoroughly embedded the Enlightenment scientists were in the slave trade—profiting from it and sometimes directly managing it. She says, “The pursuit of science and the slave trade supported one another. Scientists and slave traders worked together.”

The Two Forms of Power Were Linked

As I mulled over these two separate but related pursuits of power while writing, it became clearer to me than ever before how the idea of a mechanical Earth perfectly served both purposes: it promised control over nature and over other human beings. Two citadels of power sharing the same foundation:

The two forms of domination were linked through an ideology of a mechanical, inert Earth that, on the one hand, made possible a greater control of nature at home and, on the other, appeared to justify the superiority of English or European ways over those of Irish, African, or American natives who revered the living Earth.

The idea of a mechanistic Earth enabled every kind of power! Power for Europeans to control nature and power to compel other human beings to control it for them. With both powers in their hands, the Enlightenment thinkers/investors/traders could glimpse unlimited profits and unending human supremacy.

Where You Start Makes All the Difference

So much of the modern world still rests on this foundation of nature as machine. Our system of education is predicated on the Enlightenment idea that knowledge is objective—which can be true only if nature is made up of inert objects rather than living subjects. And if knowledge is objective, it is received from others, transferred from teacher to student, rather than built by the hard work of grappling with nature on one’s own. If knowledge is objective, students will be taught to listen to others before listening to themselves.

The modern global economic system depends on extracting “natural resources” from land that is held as property—a system that makes sense only if the ground is inert matter, not a living source growing food and providing homes for all beings who crawl and walk and fly. When people hold property, they need laws to defend it, for property begets inequality, and those who own more of it need the force of law to keep their property from being claimed by (shared with) others. So the idea of a mechanical Earth upholds a system of law designed to protect property more than to promote basic well-being and life for all.

Our modern social system, buttressed by this conception of law, channels the gifts of a generous Earth upward to benefit a few under the premise that some are intrinsically more deserving than others. Regarding some people as more worthy than others is incoherent if you start with the idea of a community of living beings, each of whom is vital to the well-being of the whole.

Why the Taboo?

When you really get how much of modern life depends on regarding Earth, and every force and being of Earth, as an “it” not a “who,” you can begin to see why the gatekeepers of education or law or money or status get nervous at the mention of a living, breathing, speaking Earth. And why there has been such a strong taboo against talking about any experiences with nature that fall outside the objective, mechanistic paradigm.

Tugging on this one thread threatens to unravel the whole fabric of modern life. It undermines every system our ancestors built to safeguard power and control.

But to survive, tug on this thread we must. These systems are destroying the livability of Earth. For this planet is the only home we will ever know, the one place in the universe where we evolved with others in a together-unfolding life.

We need systems that are resilient because they are based in sharing not profit, because they teach respect rather than raw utility, because they value reciprocity and love. Systems that operate by these values are in harmony with life and can promote the vitality of life.

Change Is Happening

Thankfully, attitudes are changing. These days I might wake up to an email from a graduate student who explains that they are designing their program around the philosophy of a living Earth. Maybe they found me while bunny-hopping through footnotes, or a professor assigned something I wrote. They are longing for some fresh academic air. Sometimes they are pushing hard against old stuck windows and doors.

But the biggest changes in academia are being brought about by Indigenous researchers and professors who are carrying Indigenous knowing straight into work. Traditional Ecological Knowledge is growing, especially in ecology and related subjects. Indigenous professors are organizing their own academic centers and labs and writing their own research methods guided by the values of Indigenous Knowledge.

Across academia there is more room, year by year, to bring holistic values into knowledge building—to talk about an openness of heart or a spiritual attentiveness that is needed if we wish to understand any phenomenon of nature. Year by year it seems more possible for students and faculty to feel connected to the animals and ecocommunities they study and to talk about that love with one another.

And outside academia, at the federal level, agencies are now enjoined to incorporate Indigenous Knowledge into their rules and decision-making. The Biden-Harris White House gathered hundreds of Indigenous individuals and groups together for consultation, and in 2022 it issued guidelines for federal agencies to integrate Indigenous Knowledge into every aspect of their work.

Indigenous Knowledge now informs federal land management, as the National Park Service explains.

Animate Earth: Safe for Work

I look forward to the day when talking about the animate Earth is free of taboo. Will education itself need to look different before that can happen? Can the practices of subjective knowing and caring for Mother Earth taught by Indigenous Knowledge achieve equal standing with the objective knowing of the Western tradition?

Many people are working toward that end. Robin Wall Kimmerer calls for Two-Eyed Seeing to build a knowledge that is up to the challenges of our current crises. “What would happen,” she asks, “if we had true stereoscopic vision, looking at the world through the Indigenous worldview as well as through the Western scientific worldview? Would we be better equipped to care for [Mother Earth] if we had both of these ways of knowing? I think that we would.”

We need knowledge that is built through engaging all the parts of the self—knowledge that grows from the heart as well as the intellect. We need knowing that arises through engaging with the others of Earth, not standing apart from them, for only this kind of knowing can guide us into wiser relations with an ever-changing Earth.

And we need to be able to talk about all kinds of experiences freely, even at work. Even in universities. When telling stories of a living Earth, stories filled with wonder and amazement and love, no longer threatens someone’s job—or gets them labeled as crazy—it will mean we have traveled a good distance away from the mindset of colonial control.

In a world that is wildly unpredictable—because it is alive—we need nimble minds and hearts. We need knowing that also breathes and changes, the kind of knowing that can bind us closer to this breathing, ever-becoming Earth.

I wrote about the taboo in higher ed because that’s where I experienced it. But I’m curious about other work settings. How does yours compare? Is there openness to other-than-rational ways of knowing? Can you talk about deeply personal experiences with nature and be heard by your coworkers? If you write, do you feel free to “go public” about them in your writing?

Please do share your thoughts and comments! I’m grateful for your kind attention all the way to the end.

For digging deeper

My path to healing the divide between intellect and spirit ran through anthropology of religion, especially the work of Graham Harvey on new animism, and the feminist environmental philosophy of Val Plumwood. Philosopher Freya Mathews helped light an intellectual path with her work on panpsychism, and I found kinship with philosophers of nature such as David Abram and Kathleen Dean Moore. Two thinkers who have influenced many by bringing spiritual awareness to issues of ecology are Thomas Berry and Joanna Macy. And of course Carolyn Merchant in The Death of Nature (1980) articulated the problem at the heart of it all.

While I was writing Kissed by a Fox I developed a few of its themes into two academic essays. Contact me if you would like a copy:

- P. Stuckey, “Being Known by a Birch Tree: Animist Reconfigurations of Western Epistemology,” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 4 (2010): 182–205.

- P. Stuckey, “The Animal Versus the Social: Rethinking Individual and Community in Western Cosmology,” Handbook of Contemporary Animism, edited by Graham Harvey (Routledge, 2013), 191–218.

On the early history of the Royal Society of London and how entangled it was with the slave trade, see M. Govier, “The Royal Society, Slavery and the Island of Jamaica: 1660–1700,” Notes and Records, Royal Society of London 53 (1999): 203–17.

A great article that talks about how Traditional Ecological Knowledge is affecting the field of science is by George Nicholas, “Western Science Is Finally Catching Up to Traditional Ecological Knowledge,” The Conversation, April 26, 2018.

Do check out John Fowler’s The Tree (1979). The Guardian called it “a blissful fusion of memoir, social history, art criticism and nature writing.”