Transcript

There’s a poison seeping through America’s veins. It’s a poison that Germany knew in the 1930s and that other countries are struggling with now as well. It’s the poison of authoritarianism.

Florida has passed laws to limit teaching about certain topics in schools—racism, African American history, gender identity, sexual orientation. The laws are worded vaguely, which gives them extra power just because they’re so ambiguous. It means they can scare people into obeying in advance to stay out of trouble. So we’re watching schools drop courses and school libraries empty their shelves of possibly offending books so that teachers and administrators can avoid being charged with crimes.

It’s a travesty, and it’s horrifying. This is a massive attack on free speech and on education—and other red states are trying to copy it. It is an organized attack on differences—as if differences among people are destructive instead of healthy and invigorating. And that’s how you know the laws are fueled by authoritarianism. They try to preserve an old order of power—where white people get to mold society into their own image. These laws are profoundly antidemocratic.

So where does the authoritarianism come from? We’ve talked before about how this country is shifting, demographically, toward more diversity—toward becoming a multihued, multicultural people. And in response, many white people are terrified. They are reacting with repression. With authoritarianism.

Karen Stenner is a political psychologist who analyzes this current wave of authoritarianism. She finds that one trait ties authoritarians together: they are uncomfortable with diversity. Authoritarians, at bottom, want everyone to be alike.

This is a little different from being conservative, she says. Conservatives are uncomfortable with change while authoritarians are uncomfortable with difference. It may sound subtle, but it leads to big differences in policies. Authoritarians emphasize obedience, she says. They try to avoid complexity. They want everyone to fit the same mold, so they pass laws to create conformity and punish diversity. They may call for expelling from the community people who are different in any way, and they are willing to use all the power of the state to enforce sameness. Authoritarians will discriminate against minorities and will try to regulate people’s behavior. So authoritarianism is fundamentally at odds with democracy in a way that conservatism—being uncomfortable with change—is not.

We might think that authoritarianism is a recent development—something that reared its ugly head in Germany a hundred years ago and is cropping up again today. But if you take a longer look at Western history, you can see that in fact it reaches way back. And in a minute we’re going to look at just how far.

But for now I want to say that trying to enforce sameness, in the long run, doesn’t work. It doesn’t work because it fundamentally doesn’t support life. For if there is one direction that nature is headed, it is always toward diversity. Endless diversity. Nature multiplies differences. Creates dissimilarity at every turn. Evolution is all about compounding differences—making out of one, many. This is the heart of the great force of life: a boundless creativity, bringing forth variations without measure, or in Darwin’s lovely words, “endless forms most beautiful.”

So no two flowers are alike, not even two petals in the same flower. No two people can ever be the same, not even identical twins. Every cell in a body, every ant in a colony, every bee in a hive, every snowflake is distinct, with its own appearance, its own journey. Nature is always bringing forth something new. Reaching toward multiplicity. Experimenting with unpredictable results.

Yet within all this diversity, there is one way in which we are all alike—inescapably alike. And we’re exactly the same in this one way only: we all die. Philosopher bell hooks wrote movingly of death as a deep equality, a gift of democracy bestowed by the Earth. “Ultimately,” she said, “nature rules. That is the great democratic gift the earth offers us—that sweet death to which we all inevitably go—into that final communion.” She added, “No race, no class, no gender, nothing can keep any of us from dying into that death where we are made one.”

It is indeed a beautiful sameness, an earthly evidence that none are or ever can be better than others. And that when one people do try to set themselves above others, it is based on a lie. The Earth shows that truth. And death is the only kind of sameness possible in an evolving, ever-shifting world.

This should be a big hint to us that trying to force people into a mold is profoundly at odds with the flourishing of life. It runs against nature’s promiscuous search for something new. The logic of sameness kills the spirit. Bullying people with authoritarianism creates only trauma and misery, not vitality and life.

Karen Stenner, the political psychologist, found that across Western countries, including the UK, the European Union, and the United States, about a third of white people have authoritarian tendencies. It sounds discouraging—a third of white people! That’s a huge bloc of people, enough to mount serious challenges to democracy. But when I read it I was surprised for the opposite reason—only a third! It’s a lot smaller number than I expected. It means that two thirds of white people in Western societies are not comfortable with authoritarianism.

This is good news because I’ve lived long enough to watch this support for diversity grow. But in the present moment we’re experiencing a backlash, and Stenner tries to figure out why. She concludes that when a society is made up of unrelated people not knit together by kinship or ethnic ties—and this means all pluralistic modern societies—people will still try to find a shared identity, a sense of “us.” And especially in times of stress, they may try to find it by falling back on an idea of sameness that is not there—by forcing sameness onto others. Stenner says this is a perennial problem—and it is, but maybe not for the reason she thinks. Stenner is a psychologist, and she finds the answer in psychology—that about a third of people will always have the temperament to want sameness.

I find the answer, instead, in history. The logic of sameness is strong today because it’s been used for so long in Western societies to help knit people into a shared identity. Authoritarianism is there like a reflex, well developed and waiting to be relied on in times of stress. Just how long, exactly, has it been used? Two thousand years, at least. The pattern goes all the way back to the Roman Empire.

So let’s look for a minute at the Roman Empire.

We tend to think of it as a pretty cosmopolitan place, and in many ways it was. It had to be!—stretching twenty-five hundred miles end to end. Romans, as they conquered each new territory, absorbed all the languages and dialects and peoples of that region. They set up a Roman-style government, but for the most part they left the local cultures alone.

With one exception. And it was a big one. Rome had a harder time dealing with foreign religions. Because Romans cared about religion. A lot. They were deeply religious. It’s a thing we’ve forgotten about the Romans—that they were so pious. They were utterly devoted to their religion—so devoted that they boasted about just how good they were at honoring the gods.

So here’s Cicero, a philosopher and statesman, writing around the year 50 BCE, during the century when the Roman republic was shifting toward an empire. He said,

If we care to compare our national characteristics with those of foreign peoples, we shall find that, while in all other respects we are only the equals or even the inferiors of others, yet in the sense of religion, that is, in reverence for the gods, we are far superior.

It was a boast that Romans repeated through the following centuries: they had the gods on their side. And the gods were on their side because the Romans were so devoted to them.

So how did the Romans show their devotion? Mainly through public rituals and ceremonies. The Roman religion centered on animal sacrifices in temples, as religions throughout the Mediterranean and Near East did at that time. Every Roman city had its temples devoted to certain gods, and every temple sacrificed animals on their front plaza as gifts to the gods. And from the animals the priests created public festivals and free public feasts to honor the gods. And everyone joined in. These were highlights of the calendar every month—days off, if you will, at a time when there was no weekly schedule.

Romans followed another kind of public ritual too: living out the traditional values handed down from the ancestors, which meant following the rules of Roman social hierarchy. Wives were to be subject to their husbands, children obeyed their parents, and slaves obeyed their masters. Stepping out of line dishonored the gods. So to stay in the gods’ good graces, everyone performed their public duties. It was a religion of doing not believing—honoring the gods so people could prosper.

We call this Roman religion “pagan,” but that’s really misleading. It conjures up images of people revering nature and going out to the forest to hold ceremonies under trees. In fact, Roman religion had almost nothing to do with the environment. Romans didn’t care at all about the natural world beyond how they could exploit it. Romans mowed down the forests to build their roads and cities, and they killed all the wild animals for games and for sport. They believed that all of nature exists to serve human beings. (Yes, this idea too goes back more than two thousand years.)

For example, Cicero in 50 BCE, right after boasting about superior Roman religion, boasted that humans are superior to all the beasts. He said that all the gifts of the Earth exist for human beings, not for the so-called lower animals, and if the animals manage to get some of the gifts, it’s only because they have stolen them from the rightful owners, meaning us. “Every thing in this world of use to us,” he said grandly, “was made designedly for us.”

But there was one way in which Roman religion echoed nature: the Roman gods and goddesses represented the forces behind nature. The fearsome sky and the wind and the wild, wild sea—these were the real masters of the universe; these were the powers that had designed the world and given it to us to use. And these were the powers that decided human destiny. Roman religion may have had nothing to do with serving visible nature, but it had everything to do with serving the invisible forces behind nature: keeping them happy by keeping the traditions handed down from the ages.

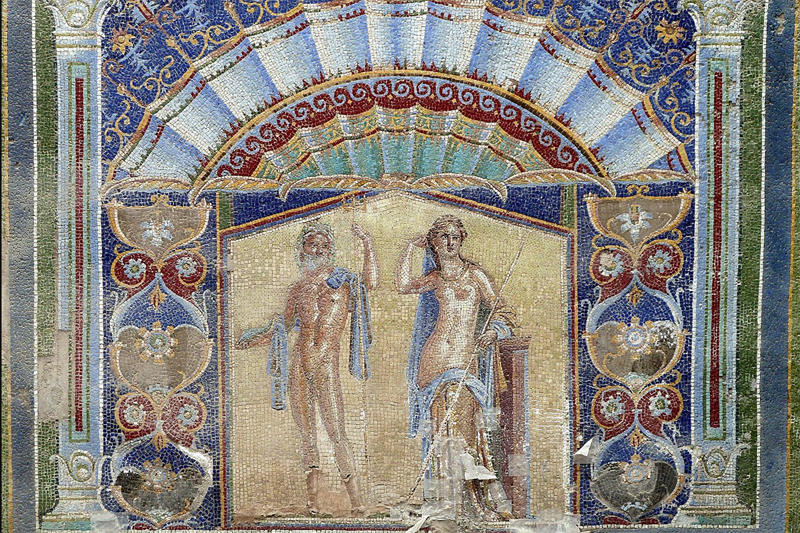

But because Romans invested so much of their identity in religion, it meant that religion acquired some of that logic of sameness. Romans expected that everyone would offer sacrifices and honor the Roman gods in the same ways. Of course, being cosmopolitan, when they absorbed a foreign culture into the empire, they absorbed the foreign gods as well. When they conquered Greece, for example, they scooped up the Greek gods and goddesses and turned them into the principal deities of the Roman pantheon. Time and again they simply folded foreign deities into the Roman religion.

But beware any people who refused to be folded in—who kept their gods outside the Roman pantheon or who refused the Roman sacrifices. Such people were thumbing their nose at the gods themselves—the powers of the universe!—which meant courting disaster on Earth. Because angry gods would punish those who abandoned them, and it could be brutal: a drought, a plague, a horde of barbarians at the city gate. To preserve the Roman peace, everyone had to follow the traditional order. Otherwise they threatened the common good.

And snubbing the Roman gods could be the first sign of sedition. Religion remained a source of anxiety for Roman emperors because it remained the Roman litmus test of loyalty—the one test of sameness in a diverse population. So when Rome got whiff of an insurrection, they focused their suspicion on the foreign religion. For instance, in the first century the Romans sailed out to a far island off the coast of Wales and massacred the Druids there because they disapproved of Druid rites. Also in the first century, they waged total war on Judaism, destroying the temple and the Jewish community in Jerusalem, because Jews were threatening independence.

And Christians too ended up on the wrong side of Rome from time to time. Christians insisted that their God did not fit into the Roman pantheon, and in fact was greater than the Roman gods. And Christians had a further strike against them: their religion was brand-new. All those foreign cults, such as from Greece, at least had the weight of tradition behind them in their own lands. But Rome had zero patience for something brand-new. If a religion had not been handed down from the ancients, it could hold nothing of truth.

So now and then—especially in tense times—local people got angry at their Christian neighbors. They accused the Christians of being atheist.

It sounds terribly odd, doesn’t it—to think of Christians as atheists? That’s because Roman religion had everything to do with how you act—how you offer the public sacrifices. But Christians avoided the public ceremonies and worshipped in private in their own homes. So they remained targets of suspicion. They were shirking their religious duties—from the point of view of Romans, not being good citizens and definitely not good neighbors.

This is just a tiny peek into Roman religion, but it should be enough to make one point clear: Even in a multicultural place like the Roman Empire, there was still one way in which everyone was expected to be the same. The Roman religion, like the hierarchical society it supported, was authoritarian in this way.

But then in the 300s the Roman order changed, and it changed fast. The emperor, Constantine, converted to Christianity, and by the end of the 300s Christianity had become the official religion of the empire.

And suddenly the tables were turned. Christianity inherited all the apparatus of power that had belonged to Rome—and it inherited as well the traditional ideas about what made for a strong and prosperous society. And number one on that list was sharing the same religion. So the new Christian emperors, starting with Constantine, followed a logic of sameness: they tried to force everyone to become Christian.

Many people think that Christianity, once it came to power, was intolerant because it was inherently rigid, but this is only partly true. Christians did consider their God and their faith to be superior to the Roman gods, and Christians were arrogant for thinking themselves more righteous than others. Some of them even demonized their non-Christian neighbors. But behind it all lay this old idea embedded in the Roman consciousness: that for society to be politically strong, everyone has to be the same in at least one way. And for Romans, that one way was public religion. So once Christianity came to power, it perpetuated that ancient pattern.

The logic of sameness is obedience.

The logic of sameness is intolerance.

The logic of sameness is violence and suppression.

And the logic of sameness continued right on down through the European history that followed the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century. It continued through a thousand years of feudalism, where children obeyed parents and wives obeyed husbands and villagers obeyed bishops and everyone obeyed God. Or at least were supposed to. And where a small class of owners got to decide the fates of others, just because they had inherited the land. And where the Christian townspeople and their local governments carried out pogroms against Jews on the basis of religion, where Europeans went on bloody Crusades against Muslims on the basis of religion, and where Christians persecuted even other Christians at home for not following the state religion. I know firsthand about this one, because my Mennonite ancestors in Switzerland were harassed for three hundred years for refusing to conform. Differences of religion remained the flashpoint of authoritarianism in Europe.

So if we wonder why a third of white people in Western countries hold authoritarian tendencies, we have a long habit of it. For most of the past two thousand years, people in Western countries have tried to find solidarity on the basis of sameness.

And the logic of sameness continues today. It undergirds all ideas of “otherness.” There can be no “other” unless everyone, in the first place, is supposed to be alike. The United States is founded on an ugly logic of sameness—the idea that Black and Native people and people of color are inferior—and many white people, about a third of us, are still uncomfortable with differences.

Passing laws to suppress differences is dangerous. When a logic of sameness is on the rise, all who are “other” are put in danger. Women and girls are not safe. People of color are not safe. Gay people are not safe. Trans people are not safe. Disabled people are not safe. Jews are not safe. Muslims are not safe. Immigrants are not safe.

It is up to the two-thirds of white people who value diversity to use the power we have to help create safety. We can speak up against authoritarianism. We can organize for voting rights. We can work to interrupt old habits of hierarchy and obedience and coercion. We can work on behalf of immigrants. We can support the rights of nature, to upend ancient ideas of human superiority. Every act toward diversity helps to challenge the old reflex toward sameness. There is something here for each of us to do.

Nature is not in the business of carbon copies. Nature, to flourish, seeks boundless diversity. Humans are not separate from the natural world, and humans should not expect to follow different rules and flourish. Just as in the rest of nature, human societies thrive not by suppressing differences but by welcoming them.

Wishing you the imagination to see a world full of differences, the heart that knows they make people strong, and the courage to help create safety in your community.

For digging deeper

“Do not obey in advance” is Lesson #1 from Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century (New York: Penguin Random House, 2017). “Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead to what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.” Obeying in advance “is a political tragedy” (17–18).

On white people soon not being the majority, see Jason Wilson, “We’re at the End of White Christian America. What Will That Mean?” The Guardian, September 20, 2017. And from William H. Frey, “The Nation Is Diversifying Even Faster than Predicted,” Brookings, July 1, 2020. For more on this, see Episode 25, “Why Doesn’t Everyone Love Diversity?”

Judd Legum at his Substack newsletter Popular Information goes into details about which books are being removed from which libraries. See “This Book Is Considered Pornography in Ron DeSantis’s Florida,” Feb. 8, 2023. Chris Geidner in Law Dork offers a great overview of the laws that stifle free speech in education: the Stop WOKE Act, the Don’t Say Gay law, and H.B. 1467. See “Florida’s War on School Speech, a Law Dork Q&A.”

Karen Stenner’s book is The Authoritarian Dynamic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). For a summary of her research, and for a portrait of the authoritarian political style, see the chapter by Karen Stenner and Jonathan Haidt, “Authoritarianism Is Not a Momentary Madness, but an Eternal Dynamic Within Liberal Democracies,” in Can It Happen Here? Authoritarianism in America, ed. Cass R. Sunstein (New York: William Morrow, 2018), 175–220. That chapter is available for download from a link in the Publications section of Karen Stenner’s home page.

“Endless forms most beautiful” comes from the end of Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species: “whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” Available free online at Project Gutenberg.

bell hooks’s essay “Earthbound: On Solid Ground” appears in her book Belonging: A Culture of Place (London: Routledge, 2009), 116–20. The whole book is a treasure. Her chapter “Returning to the Wound” reflects on fellow Kentuckian Wendell Berry’s 1968 book on racism, The Hidden Wound. Her words are so beautiful they inspired the very start of this podcast; see Episode 1, “Earth Is Our Witness.”

Cicero boasting about Roman piety comes from De Natura Deorum (On the Nature of the Gods), trans. H. Rackham (Harvard Univ. Press, 1933), 2.3.8. Available free online at the Internet Research Archive.

Mary Beard in SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome (New York: Norton, 2015) emphasizes the multiculturalism of the Roman state. By the first century, even the senate of Rome was a multicultural body. Beard also quotes another Roman boast about religion from the second century BCE. It was carved into marble and placed in the center of a conquered Greek town in Turkey:

The fact that we Romans have, absolutely and consistently, judged reverence towards the gods as of first importance is proved by the favour we have received from them in this account. . . . . We are quite certain . . . that our high respect for the divine has been evident to everybody. (102)

That is, it’s obvious that we conquered you because the gods like us better than you because we show them more devotion.

Cicero on humans and nature:

Thus, as the lute and the pipe were made for those, and those only, who are capable of playing on them, so it must be allowed that the produce of the earth was designed for those only who make use of them; and though some beasts may rob us of a small part, it does not follow that the earth produced it also for them. Men do not store up corn for mice and ants, but for their wives, their children, and their families. Beasts, therefore, as I said before, possess it by stealth, but their masters openly and freely. It is for us, therefore, that nature hath provided this abundance. . . . Beasts are so far from being partakers of this design, that we see that even they themselves were made for man.

Cicero also boasted about controlling nature:

We are the absolute masters of what the earth produces. We enjoy the mountains and the plains. The rivers and lakes are ours. We sow the seed, and plant the trees. We fertilize the earth. . . . We stop, direct, and turn the rivers: in short, by our hands we endeavor, by our various operations in this world, to make, as it were, another nature.

Both quotes from On the Nature of the Gods, trans. C. D. Yonge (1877), 2.150–58, available free online at ToposText.org.

One example of imperial anxiety about religion comes from the early 200s. Dio Cassius, a friend of the soon-to-be emperor Octavian, gave a speech addressed to the ruler about how to run a good monarchy. In it he said,

You should not only worship the divine everywhere and in every way in accordance with our ancestral traditions, but also force all others to honor it. Those who attempt to distort our religion with strange rites you should hate and punish, not only for the sake of the gods, . . . but also because such people, by bringing in new divinities, persuade many folks to adopt foreign practices, which lead to conspiracies, revolts, and factions, which are entirely unsuitable for monarchy.

From Dio Cassius, History of Rome, 52.36.1–2, quoted in C. Kavin Rowe, World Upside Down: Reading Acts in the Graeco-Roman Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 165.

To get a lively feel for just how deeply Romans valued tradition and just how much they mistrusted and despised new upstart religions, see Robert Louis Wilken, The Christians as the Romans Saw Them, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), especially chapter 3, “The Piety of the Persecutors.” The charge of Christians as atheists comes from chapter 4, “Galen: The Curiosity of a Philosopher.”

Elaine Pagels too writes about how Christians were called atheists in The Origin of Satan (New York: Random House, 1995), especially chap. 5, “Satan’s Earthly Kingdom: Christians Against Pagans.” In that chapter she draws a fascinating contrast between the thinking of the Christian philosopher Justin Martyr, ca. 140 CE, and Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-emperor, 161–80 CE. Justin Martyr does not come off well: he engages in “us-them” thinking to the extent of demonizing all followers of the traditional Roman religion. Only Christians, in his view, are following a divinely inspired way; all others are motivated by demons.

Tacitus (in The Annals 14.29–30) reports how the Roman general of Britain, Suetonius Paulinus, massacred the Druids on the remote island of Mona, present-day Angelsey in the northwest corner of Wales, during the first century CE. I’ve mentioned the Roman persecution of Druids on this podcast before, in Episode 25, “Why Doesn’t Everyone Love Diversity?” and Episode 29, “Where Did We Go Wrong?”

More details of Roman religion and persecution of Jews and Christians can be found in W. H. C. Frend, Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church (Blackwell, 1965). Roman attitudes toward foreign religions appear in chap. 4, “Rome and Foreign Cults.” If not available at a library near you, the book is available at the online textbook subscription service Perlego.

For intolerance and religious violence during the fourth century and later by Christians as well as pagan Romans, see Bart D. Ehrman, The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), chapters 8 and 9. He reports that Constantine built his new city of Constantinople by looting Roman temples, ripping the gold plating off the holy statues, and melting down the gold to decorate his city. Constantine wrecked five Roman temples to build Christian churches on those sites. His son, who became emperor after him, outlawed all the old Roman sacrifices. One line from his new law code read: “Anyone who sacrifices or worships images shall be executed.”

The three-hundred-year story of harassment of the Mennonites in Bern comes from Christian Neff and Isaac Zürcher-Geiser, “Bern (Switzerland),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (1986). In 2017 a Bern official apologized to Mennonites and asked forgiveness for the government persecution.

A society that practices authoritarianism is by definition opposed to individual freedom; an authoritarian community tries to create and enforce sameness. So there is a longstanding tension in Western history between the individual and community, as if they are opposed to one another rather than supporting each other, as they do in some other cultures, especially Indigenous ones. I explored this in Kissed by a Fox, especially chapters 4–6, with examples from West African thought and practice. See also Episode 15, “Reimagining Community.”

The logic of obedience still reigns in, for instance, dog training, or it did until very recently. Many people still think that training dogs is more about giving commands than it is about cultivating a loving and connected relationship. I wrote about this in the chapter “Sapphire” in Kissed by a Fox.

Thank you Priscilla, I really enjoyed you blog. Emperor Constantine did his best to enforce an Orthodox “Uniform Christian Belief” in the Nicaean creed from 390 AD. To day almost all of the worlds Christians recite this creed every Sunday morning. However this creed says almost nothing about the humility of Jesus who taught acceptance of individuals by forgiving them and spreading faith, love and compassion to everyone. The “church” founded by Constantine and those who followed, called everyone who did not follow Orthodox belief “hereticts” and had them burned at the stake. The Church of the 17th century even burned scientists at the stake for promoting the “false” belief in a sun centered solar system which the Church claimed conflicted with the account of creation given in the Bible. To this day the scientists have not forgiven the Church and the Church only said they were sorry 400 years too late.

Growing up Mennonite, as part of the pacifist Anabaptist tradition, I learned early on about the difference between Jesus’s teachings and the Christianity of empire. The Constantinian church councils, in trying to hammer out an agreement on what all Christians believed, had the unintended and truly perverse permanent result of defining a Christian as someone who believes certain things, not someone who follows Jesus. Those councils turned Christianity toward what it is today, a religion defined more by thinking (right belief) than by being (right living). People can call themselves Christian today just because they believe a, b, and c, while acting in complete opposition to the life and teachings of Jesus. An example is white Christian nationalism. It is truly astounding and tragic what happens when a religion gets centered on tenets of thought instead of on the presence of aliveness and love in the heart—and then when that same religion acquires the political power of an empire to enforce its will.