Transcript

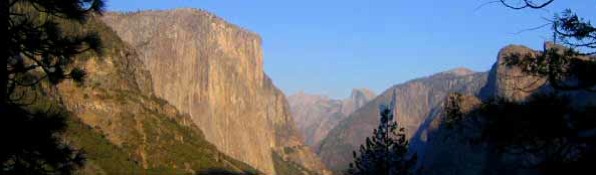

We step down the slope of wet sand. Today the waves are small, breaking in soft foam around our ankles. We wade in deeper, settle our snorkel masks on our faces, and lift our feet from the sand, floating toward our local reef.

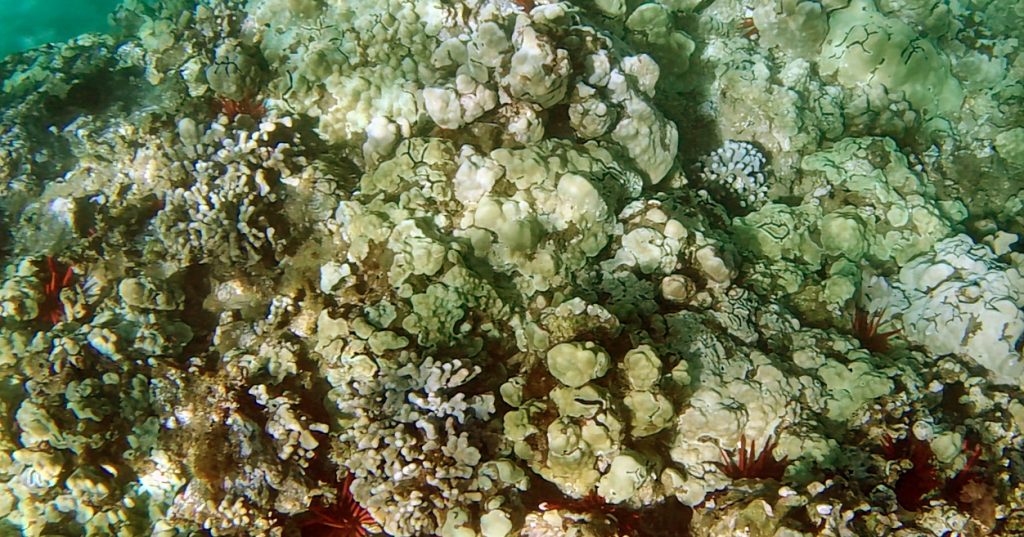

My eyes roam over the rolling stretches of coral below us. About three acres in size, this reef is covered with mounds and rills, spires and valleys, mushroom-shaped domes and craggy cliffs. Each rock that rises in turn as we float past is punctured by lacy cutouts and decorated with jutting ledges. And much of the surface of this reef is splashed as if with yellow paint—the bright yellow of lobe coral.

Lobe coral is only one of several kinds of coral here, part of the community of millions living on this reef. Hundreds of types of animals and plants are here, from sharks and barracudas and turtles and eels to tiny yellow tang, like bright triangles of yellow sunshine darting among the crevices. I keep a list of the species we’ve seen at this reef, and it’s already over a hundred, and we haven’t even started on plants! More than seven thousand different plants and animals inhabit Hawai’i’s reefs as a whole.

Lobe coral is only one of several kinds of coral here, part of the community of millions living on this reef. Hundreds of types of animals and plants are here, from sharks and barracudas and turtles and eels to tiny yellow tang, like bright triangles of yellow sunshine darting among the crevices. I keep a list of the species we’ve seen at this reef, and it’s already over a hundred, and we haven’t even started on plants! More than seven thousand different plants and animals inhabit Hawai’i’s reefs as a whole.

This rolling seascape is an alien place, home to millions of creatures who can breathe water rather than air, who can survive the thrashing of stormy currents and towering waves. But on a calm day like this, our reef also looks like a fairy castle, with bright turrets and secret passages, and looking down at it as we float by, I find myself wanting to be a tiny fish just to swim through that dazzling maze.

A reef has been called the “rainforest of the sea,” and like a rainforest, it is most healthy when it’s most diverse. Ecologists tell us that diversity makes a region more stable—more resistant to diseases and more able to tolerate climate change.

Diversity has the same benefits among human beings. And yet diversity is the single most challenging social issue we face in this country today. Because today, white people are dragging our feet. A significant portion of us are afraid of diversity.

Part of the fear has to do with how fast the makeup of the country is changing. And it is unusually fast. In 1976, when I was in college, white Christians made up more than 80 percent of the country. Forty years later, in 2017, white Christians made up less than half. From eight-in-ten people to four-in-ten is a dramatic shift, especially when it happens in only forty years. By 2045, we’re told, the country as a whole will be majority minority, with white Americans less than half of the population for the first time ever.

So white racial anxiety is rising. Just since January, white people have introduced hundreds of laws across dozens of states to make it harder for people of color to vote. White parents are panicking that their children will learn about racism in school. And a new study shows that the main motivation among the rioters who stormed the Capitol on January 6 was white fear. Fear of “white replacement.”

Just a rapid increase in ethnic diversity would be enough to cause social upheaval. But, as a country, and as white people in particular, we’re also dealing with another factor: we don’t have good mental models for diversity.

It’s a history problem. Because for nearly two thousand years, Western societies followed an authoritarian model of society. And what scholars of authoritarianism tell us is that the what is most important to authoritarians is similarity. People have to be alike. Unity is bought through sameness.

The point comes from political psychologist Karen Stenner, in her book The Authoritarian Dynamic. She says that authoritarians are different from conservatives. While conservatives resist change, authoritarians resist diversity. Authoritarianism is about intolerance.

So if we look back through Western history, we find a fairly steady pattern of intolerance stretching all the way back to the Roman Empire. But here’s the part that surprises most people: it goes back to the pagan Roman Empire, before Christianity. The Roman Empire from its very first century was in the habit of outlawing any ethnic or religious group that it suspected of becoming a threat to its power.

By the year 54 CE, for example, Rome had outlawed the native Celtic rites of the Druids in central Europe. Around that same time, in the year 49, the city of Rome expelled Jews—already the third time in its history it had done so. And then in the year 66 Roman forces crushed a Jewish independence movement in Judea and destroyed the Temple in Jerusalem. The emperors went on to try to destroy Christianity many times over the next few centuries.

Just how intolerant was Rome? In the early 200s, a friend of the soon-to-be emperor Octavian gave a speech addressed to the ruler about how to run a good monarchy. In it he said, “You should . . . worship the divine everywhere and in every way in accordance with our ancestral traditions.” In other words, everyone should be alike in following the old religion. “You should force all others to honor” the old ways, he said, and anyone who didn’t should be punished. Why punished? “Because such people, by bringing in new divinities, persuade many people to adopt foreign practices, which lead to conspiracies, revolts, and factions, which are entirely unsuitable for monarchy.”

There’s a lot to notice here: fear of foreigners, fear of religious difference, and above all fear of losing political control. Diversity could lead to revolt. Differences are dangerous.

So when Christianity became the religion of the empire in the late 300s, it inherited this long system of intolerance. And it added its own technique for controlling people in the form of a new church doctrine that grew out of the internal struggles of one man.

I told some of this story in Kissed by a Fox—how one bishop’s conscience came to hold enormous sway over Western thought for two thousand years. When he was a young man, the bishop Augustine had wrestled with his demons and had felt powerless to overcome them. He came to believe that human beings do not have the power to choose good—that we are predisposed always to choose evil. His idea came to be called “original sin,” and it has shaped Western thought down to this day.

Original sin acted like a new concrete foundation getting poured under the old house of empire. Because if humans are powerless to choose what is good, we always need someone or something bigger than us to nudge us—or force us—toward goodness. And for more than a thousand years after Augustine, church and state both were happy to be the enforcers.

These were the centuries of feudalism, when society was organized in a strict hierarchy and most of the people lived at the bottom and worked the land as serfs.

A thousand years of serfdom changes people. It trains them to think in terms of obedience to authorities above them. So eventually it looks like society can’t function any other way. Authoritarianism looks natural. The right of kings to rule looks divinely ordained.

I can’t help but think here, as I’ve said before, of Vine Deloria Jr. of the Standing Rock nation, who opened my eyes to the authoritarianism that we white people have inherited from European history, and especially from a thousand years of feudalism. Deloria wrote, “Feudalism saw man as a function of land and not as something in himself. . . . Far easier than the Indian tribes of this [North American] continent, the Europeans gave up the ghost and accepted their fate without questioning it. And they remained in subjection for nearly a millennium.”

Part of that subjection during those thousand years involved suffering Inquisitions, as the Church tried to destroy groups it called heretics. From about the eleventh century on, the Church also organized Crusades to whip up hatred of Muslims and make war on Muslims in Jerusalem. The hate rhetoric intensified hatred closer to home, so that from the time of the Crusades, violence against Jews in Europe increased. The Church forcibly converted Jews, and local townspeople attacked Jewish communities and expelled Jews, from one city and town after another, over centuries. It’s a shameful history based on fear of difference. On the idea that safety and cohesion depend on similarity.

So when diversity broke out in a big way during the Protestant Reformation, starting in 1500, the authorities worked even harder to suppress it. They tried to create uniformity within each territory, and they tried within each church to make people conform. I have a personal interest in this history, because my ancestors took part in both kinds of social control; they were on both the giving and receiving ends of it. Here’s how it worked.

The Protestant Reformers were often highly educated young men who had been trained in theology. And almost to a man, they loved Augustine and his doctrine of original sin. They fully agreed that people are disorderly by nature and needing to be controlled.

In fact, the Reformers complained that the Catholic Church wasn’t doing a good-enough job of controlling people. They saw problems of alcoholism and domestic violence, and they analyzed all these as moral failings. A lack of discipline. So they set up systems of discipline within their congregations.

This was especially true of John Calvin. In his churches—which means throughout the territory of what is now Switzerland—committees of elders and pastors would visit every home several times a year to make sure people were ready to take communion. Anyone who didn’t clean up their lives would be barred from communion. And if they refused to reform, they would get kicked out of church for good.

To give you a flavor of how Calvin wrote about church discipline, here is a paragraph from his magnum opus, published when Calvin was all of twenty-seven years old. The paragraph starts,

For what will happen if each is allowed to do what he pleases?

It’s a rhetorical question, of course; people doing what they please is exactly the problem! So people need to be admonished.

Therefore [he writes], discipline is like a bridle to restrain and tame those who rage against the doctrine of Christ; . . . and also sometimes like a father’s rod to chastise mildly and with the gentleness of Christ’s Spirit those who have more seriously lapsed.

The picture is clear—of keeping people in line by force, because humans, like horses, have to be controlled, and children have to be spanked.

My Mennonite ancestors in Switzerland in the 1500s adopted this same process of discipline in their churches. And the more conservative among them practiced church discipline and excommunication right down into my lifetime, and I have watched it in action and could tell a few harrowing stories.

But my Mennonite ancestors were also on the receiving end of the authoritarian whip—and literally. I said that during the Protestant Reformation they chose to become Anabaptist rather than Calvinist. But in the region where they lived, the canton of Bern in what is now Switzerland, this was a huge no-no because the authorities had decided that all of Bern would be Calvinist. Because, unity through sameness, right?

So the authorities in Bern worked hard to rid their territory of Mennonites. Every few years they took up the job all over again. They would arrest and jail some, whip others, and confiscate possessions. They tried branding them, expelling them from their homes, sending them across the border into exile. They even sentenced men to galley-slavery, to be chained to the oars in the dark galley of a ship for years on end alongside other convicts. One time the authorities tried to deport the whole group of Bernese Mennonites to India, but when they wrote to the East India Company for passage on their ship, the company never wrote back.

This pattern of harassment and persecution went on for three hundred years. It wasn’t until the early 1800s that the Bern government finally granted tolerance to the Mennonites.

Tolerance is a recent accomplishment in Western history. It’s been so much easier to fear difference. To want to be surrounded by people like us. To drive out those who are different.

When a people’s history is dominated by authoritarianism, it becomes very hard to imagine a different way. This long history helps to explain why American “rugged individualism” often has a reactionary flavor: “you can’t tell me what to do.”

A community based on conformity and control can never bestow freedom. This is one reason why a sense of community is so rare in this country today. A legacy of authoritarianism poisons our efforts to create community. Americans today flee community while longing for it at the same time.

Karen Stenner, in The Authoritarian Dynamic, shows that about a third of white people across all Western nations prefer authoritarianism and are truly uncomfortable with diversity. She calls this tendency toward authoritarianism an “eternal dynamic,” something we can’t change.

I disagree. It is a problem of history. For white people, authoritarianism is a cultural habit we learned from long centuries stretching back at least to the Roman Empire. The pattern took generations to develop, and it will take generations to unwind and heal.

The good news is, healing is possible, even on a broad social scale. I lived in California during the nineteen eighties and nineties, when the numbers of Latinx people were growing and white people were on track to become a minority by the year 2000. As Anglo dominance waned, voters passed hateful laws against immigrants and Spanish language use. But a lot of people rallied for change—to increase voter registration, to work for immigration reform, to make local communities welcoming places. The same is possible in the country as a whole. But it will take some effort, some work. Democracy needs our ongoing attention and care.

It will also take effort to unwind the logic of authoritarianism—the dogma in science, for instance, that has led us to see nature as endless competition between individuals and to remain blind until very recently to the cooperation and nurturing that flow back and forth in communities of trees and plants and animals.

It will take effort to unwind the authoritarian logic in monoculture, where lack of diversity weakens our food crops, and to end the authoritarian cruelty of factory farms.

It will take generations to unwind the logic of caste and inequality. The logic of gender norms and conformity. The logic of policing and punishment. The logic of racism.

I have a fantasy—that people who are frightened of diversity could go sit in a forest and bathe in its peaceful atmosphere. Could breathe in the healing esters of the trees. Could feel their body’s stress levels drop and a sense of letting-be steal over them. “Forest bathing” is well known from Japan; less well known is the tradition of Waldeinsamkeit from Germany, or “forest solitude”—going out alone into a forest to find peace.

I wish frightened people could sit in a quiet spot under a tree or beside a creek and contemplate the rich gift of life flowing through their veins. Could float over a reef with its hundreds of species, its millions of individual lives, and marvel at the bright colors and shapes—gifts of millions of years of diversity. I wish people could know, really know, how the life in their own veins depends on the life flowing through the veins of others. Could reassure themselves that the same life flows in all.

“This person is like me in wanting to be happy” is a phrase I learned once in a Buddhist meditation. It’s a phrase to meditate on when we’re tempted to feel frightened by difference. “This person is like me in wanting to be happy.”

The Great Heart of the universe is beating everywhere—in sea turtles and corals and algae, in forests and frogs and streams. And in human beings. Every last one of us.

For digging deeper

A great photo of lobe coral looking very much like it does at our reef is at the “Lobe Coral” page at the University of Hawai’i Waikiki Aquarium site.

For studies on benefits of human diversity, see “How Diversity Makes Us Smarter,” by Katherine W. Phillips, Greater Good Magazine, September 18, 2017.

US population numbers come from Jason Wilson, “We’re at the End of White Christian America. What Will That Mean?” The Guardian, September 20, 2017. And from William H. Frey, “The US Will Become ‘Minority White’ in 2045, Census Projects,” Brookings, March 14, 2018.

Robert Pape of the University of Chicago discussed the new demographic study of the insurrectionists in “The Capitol Rioters Aren’t like Other Extremists,” by Robert A. Pape and Keven Ruby, The Atlantic, February 2, 2021. I enjoyed his interview on Amanpour and Company on May 6, 2021, “A New Study Shows Us the Single Biggest Motivation for the Jan. 6 Rioters.”

Karen Stenner’s book is The Authoritarian Dynamic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). A brief form appears in a chapter by Karen Stenner and Jonathan Haidt, “Authoritarianism Is Not a Momentary Madness, but an Eternal Dynamic Within Liberal Democracies,” in Can It Happen Here? Authoritarianism in America, ed. Cass R. Sunstein (New York: William Morrow, 2018), 175–220. That chapter is available for download at this link. In that chapter Stenner and Haidt call authoritarianism an “eternal dynamic,” but I disagree, as will become clear; I think it’s a problem of history.

I explored the long reach of Augustine’s doctrine of original sin, and especially how it warped Western science’s thinking about the natural world, in Kissed by a Fox: And Other Stories of Friendship in Nature. My academic paper on this topic is “The Animal Versus the Social: Rethinking Individuals and Community in Western Cosmology,” in The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, ed. Graham Harvey (Durham, UK: Acumen, 2015), 191–208. And we talked in an earlier podcast about the limitations of Western conceptualizations of community in the episode “Reimagining Community.”

On the expulsions of Jews from Rome in the Republic and early Empire, see Silvia Cappelletti, The Jewish Community of Rome: From the Second Century B.C. to the Third Century C.E. (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 39, 87–88.

The emperor’s counselor was the historian Dio Cassius, and he recorded his speech from the early 200s in his History of Rome, 52.36.1–2, quoted in C. Kavin Rowe, World Upside Down: Reading Acts in the Graeco-Roman Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 165. The whole paragraph reads,

You should not only worship the divine everywhere and in every way in accordance with our ancestral traditions, but also force all others to honor it. Those who attempt to distort our religion with strange rites you should hate and punish, not only for the sake of the gods, . . . but also because such people, by bringing in new divinities, persuade many folks to adopt foreign practices, which lead to conspiracies, revolts, and factions, which are entirely unsuitable for monarchy.

Vine Deloria Jr.’s comments come from Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (1969; reprint Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988), 175. Feudalism operated in the US too, which led to the Anti-Rent Wars in New York the 1830s and ’40s. New York’s feudalism wasn’t dismantled until the Civil War.

For more on Calvin’s pattern of church discipline, see Philip S. Gorski, The Disciplinary Revolution: Calvinism and the Rise of the State in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003). Quote is from John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, bk. 4, chap. 12. The technique of banning people from communion is still practiced in the Catholic Church today—or at least the American Catholic bishops threatened it against Joe Biden this week.

The sorry saga of the Mennonites in Bern comes from Christian Neff and Isaac Zürcher-Geiser, “Bern (Switzerland),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (1986). In 2017 a Bern official apologized to Mennonites and asked forgiveness for the government persecution.

Steven Levitsky talks about how dangerous rising authoritarianism among white Republicans is, and what to do about it, in “How Democracies Die,” 2021 Global Studies Lecture, Alfred University, Feb. 28, 2021. The talk is based on his and Daniel Ziblatt’s book, How Democracies Die (New York: Crown, 2018).

For forestry science research into the communication between trees, see Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest (New York: Knopf, 2021). Her research counters what she calls “overly authoritarian and simplistic” forestry practices. I especially enjoyed her TEDxSeattle talk, “Nature’s Internet: How Trees Talk to Each Other in a Healthy Forest,” November 2016, where she says, “In an ecosystem, there is no bigotry. There’s only reciprocity. Only mutual respect.”

Highly bred crop varieties can no longer communicate with their plant neighbors and call in defenses against pests, as reported by Heather Kirk, “Commercial Corn Varieties Lose Ability to Communicate with Their Own Defenders,” Ecotone, Ecological Society of America, Oct. 27, 2011. I found this research in Peter Wohlleben’s book The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate. Discoveries from a Secret World, trans. Jane Billinghurst (Vancouver and Berkeley: Greystone Books, 2016).

For the benefits of forest bathing, see the study by Bum Jin Park et al., “The Physiological Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Taking In the Forest Atmosphere or Forest Bathing): Evidence from Field Experiments in 24 Forests Across Japan,” Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine 15, no. 1 (Jan 2010): 18–26. I just learned about Waldeinsamkeit because it became popular again over the pandemic. See Mike MacEacheran, “Waldeinsamkeit: Germany’s Cherished Forest Tradition,” BBC Travel, March 15, 2021.