In a recent interview on 13.7, NPR’s opinion blog about “Cosmos and Culture,” theoretical physicist Marcelo Gleiser says,

Spirituality is a word that has been kidnapped by religion and that invokes the existence of supernatural spirits and the like.

He sees things differently:

I use the word in a very different way, as an expression of our awe of nature, of our attraction to the mystery of existence, to something intangible. The more I learn about nature, the more spiritually connected I feel to it, as I see myself as part of something grander than we are.

Gleiser is describing a growing form of nature spirituality—spirituality without spirits. Many call it religious naturalism, or allowing nature to be the focus and extent of spirituality. Nature as the All. In religious naturalism wonder and awe grow out of taking part in the processes of nature, contemplating the vast mysteries of the natural world.

Gleiser is a good spokesperson. He says,

That’s what we should all be after, trying to expand our mindfulness, to connect with a grander reality, mysterious and unknowable.

I like this view. I like it a lot. I might even count myself among its adherents. Religious naturalists talk my language when it comes to appreciating the intricacies of the natural world, connecting with nature through mindful awareness, and allowing nature to guide our reflections and our actions.

Spirituality without spirits

As people move farther away from the idea of a God outside nature, spiritual forms of naturalism are emerging all around. Atheistic Pagans  recently published a book about it. The Dalai Lama teaches the Buddhist form of it—emptiness, or the failure of any one thing to exist independently of other things. Secular chaplains and humanist celebrants perform weddings and conduct funerals without reference to any kind of spirit or unseen power.

recently published a book about it. The Dalai Lama teaches the Buddhist form of it—emptiness, or the failure of any one thing to exist independently of other things. Secular chaplains and humanist celebrants perform weddings and conduct funerals without reference to any kind of spirit or unseen power.

What most of these variations share is wanting to distance the spiritual impulse from spirits, or the idea of unseen entities outside nature.

I have two problems with this: I don’t experience nature as devoid of spirits, and neither do I experience spirits as outside nature.

Let me explain.

Spirit as aliveness

Think of someone dear to you—a friend, a family member. You know them well. You would recognize them anywhere by the tilt of the head, the lift of a shoulder. When you are separated from them, you miss their quirky sense of humor.

This is what it means to know someone—to recognize their personality, their character.

Or in other words, their spirit.

In this sense spirit is more like personality. Aliveness. Your spirit is your particular way of being alive. Not some spooky, nonphysical part of you, it is you—quirky you. Your person, your spirit—the most natural thing in the world.

Personality everywhere

Now suppose every being of nature is more like you—full of personality or aliveness or intelligence—than like a chair. It’s easy to appreciate  Antz, by mimathology, Flickr, Creative Commons license intelligence in animals. But insects too have their own kinds. Ants navigate by following more types of cues than humans do—sun position, polarized light, subtle shifts in odors, surface texture, and step-counting.

Antz, by mimathology, Flickr, Creative Commons license intelligence in animals. But insects too have their own kinds. Ants navigate by following more types of cues than humans do—sun position, polarized light, subtle shifts in odors, surface texture, and step-counting.

Or take plants, finally getting respect for their abilities to taste and smell and hear and make decisions. Even slime mold can compute the most efficient pathways between complex arrays of targets. Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist at SUNY and a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, told Krista Tippett of On Being,

I can’t think of a single scientific study in the last few decades that has demonstrated that plants or animals are dumber than we think. It’s always the opposite, right? What we’re revealing is the fact that they have a capacity to learn, to have memory, and we’re at the edge of a wonderful revolution in really understanding the sentience of other beings.

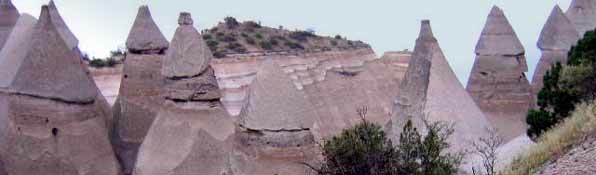

It’s easy to sense that places have personality too. Pausing in the stillness of a redwood forest gives you a different experience than pausing next to pounding surf. Each place has its own character. A forest develops its particular feel in part by sharing nutrients and chemical signals among the various trees and plants. Perhaps each place performs its own version of chemical sharing. However it happens, each place has its own way of being alive—its own character, its spirit.

It’s easy to sense that places have personality too. Pausing in the stillness of a redwood forest gives you a different experience than pausing next to pounding surf. Each place has its own character. A forest develops its particular feel in part by sharing nutrients and chemical signals among the various trees and plants. Perhaps each place performs its own version of chemical sharing. However it happens, each place has its own way of being alive—its own character, its spirit.

Body implies spirit

Do I believe in spirits? You bet I do. I find aliveness everywhere. Where matter and spirit are joined, spirit permeates all creatures, including so-called inanimate parts of nature.

To be is to be spirit. You, I, insects, trees, rocks—we’re all matter; we’re all spirit. Body implies spirit—a way of being.

Acknowledging spirits rather than trying to rid ourselves of them will give us more tools for addressing the dire ecological straits we are in today. In fact, acknowledging spirit may be the only way to solve these problems. Why? Because it requires recognizing that more-than-human others have character too—and are characters in their own stories. Each creature or part of nature offers priceless and irreplaceable ways of being.

Acknowledging spirits rather than trying to rid ourselves of them will give us more tools for addressing the dire ecological straits we are in today. In fact, acknowledging spirit may be the only way to solve these problems. Why? Because it requires recognizing that more-than-human others have character too—and are characters in their own stories. Each creature or part of nature offers priceless and irreplaceable ways of being.

If the old natural-supernatural divide is outdated, as I wrote before, there’s no need to renounce spirits. Spirits instead can mean different ways of being alive.

Not supernatural, spirit is part and parcel of nature—the very heart of nature.

For more on relating to nature in personal terms, see the first chapter of my book, Kissed by a Fox: And Other Stories of Friendship in Nature (Counterpoint, 2012). I have learned much about nature and spirit from American Indian philosophers and writers. See, for example, an essay of Vine Deloria Jr. of the Standing Rock Sioux nation, “If You Think About It, You Will See That It Is True,” in Spirit and Reason: The Vine Deloria Jr. Reader (Fulcrum, 1999).

I use the word in a very different way, as an expression of our awe of nature, of our attraction to the mystery of existence, to something intangible. The more I learn about nature, the more spiritually connected I feel to it, as I see myself as part of something grander than we are.

I use the word in a very different way, as an expression of our awe of nature, of our attraction to the mystery of existence, to something intangible. The more I learn about nature, the more spiritually connected I feel to it, as I see myself as part of something grander than we are.

Yay Priscilla. This is great. I love the way you’ve put these ideas together.

Thanks, Linda! Glad you dropped by. The popular ideas about spirit simply reinforce that old dualistic split between matter and spirit, so I hope people find this helpful.

Dear Priscilla,

I came to your blog searching for writings on the spiritual and its relationship with and beneficent gift it can give to the modern world of men. I am greatly encouraged.

Thank you for presenting a bold and passionate defence of the great intrinsic worth of Nature and the deep spiritual aspect that Nature has upon this Earth.

I am particularly encouraged by your understanding that Spirit and the Material are neither separated nor mutually exclusive.

My own faith (spirituality, if you like) is both complex and extremely simple. Of a Christian upbringing and life, primarily of the Protestant tradition, I was always dissatisfied with the dismissal and denigration of a myriad of aspects of Creation and man’s part of it. From the sidelining and suppression of the feminine principle; to the ignorance of the great worth of traditional, nature-connected societies; to the calling evil or non-existent the spirits which Christians cannot comprehend, such as the elemental spirits and the spirits of the sun, moon and stars: I found that I had great need to absent myself from the Church for a time.

I still follow Jesus Christ as my Lord and elder Brother, and believe in the Holy Trinity, which I now know as the Holy Family of Father, Mother and Son. My understanding of this, my Family, is that They are both external – dwelling as They do in the heavenly realms – and internal, dwelling as They do within all Their Children.

I am now in a process of entering the Orthodox Church, a tradition very much rooted in the thinking of the ancients and far less tainted – my dear Orthodox sister at the Greek Orthodox Church I attended last Lord’s Day delicately put it, “diluted” – by the modern mindset and ways.

I would like to encourage you in your very worthwhile endeavours.

Blessings,

Pippin T.

Thank you for stopping in, Pippin. Much joy to you in your chosen path.