I went on a pilgrimage a while back, revisiting my home state of Ohio. I say “revisiting” because on that trip I saw a side of Ohio I had never seen before: sacred sites built by the first people of the land. The highlight was an enormous earthen effigy mound in southern Ohio called Serpent Mound—a place I’d never heard of in all my growing-up years.

I have an oddly clear memory from junior high: Mr. Vershum in 1970 with blond hair and bushy broad sideburns standing in front of a room of seventh-graders, trying (in vain) to teach us Ohio history. He told us to open our textbooks. There, on the first page, I saw the date: 1803, the year Ohio became a state. As if nothing at all had happened before then.

All us kids knew that other people had lived there before us. My dad owned evidence—two or three arrowheads picked up from lawn or fields, their sides finely chipped to a razor-sharp edge, their points always broken off as if tossed away the moment they’d snapped in the middle of a hunt.  We’d all heard about the Great Black Swamp that oozed in our flat northern part of the state before European settlers chopped down the hardwood forest, drained the land, and planted the sweeping miles of corn and soy that now surrounded us. A few families had even passed down stories of Indians from the early days.

We’d all heard about the Great Black Swamp that oozed in our flat northern part of the state before European settlers chopped down the hardwood forest, drained the land, and planted the sweeping miles of corn and soy that now surrounded us. A few families had even passed down stories of Indians from the early days.

But nothing about arrowheads or first people or forced evictions appeared in the official history. If our textbooks were to be believed, the Indigenous people had never existed.

And so I never learned either that ancient Natives built massive earthworks about two thousand years ago. I didn’t know that these mounds continue to rise above ground today and that you can visit them.

Serpent Mound

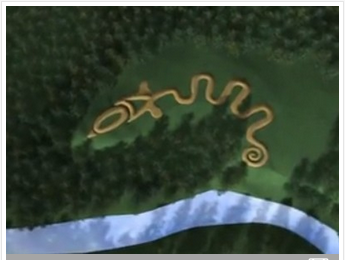

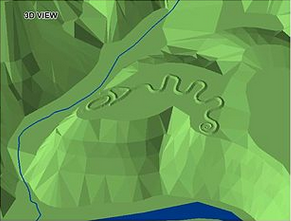

Serpent Mound meanders in graceful curves along a bluff overlooking a river in the rolling land of southern Ohio. The serpent rests in an oxbow of river channels, its head reaching the very tip of the land, as if it has traveled to the end of earth and now might launch into some great unknown.

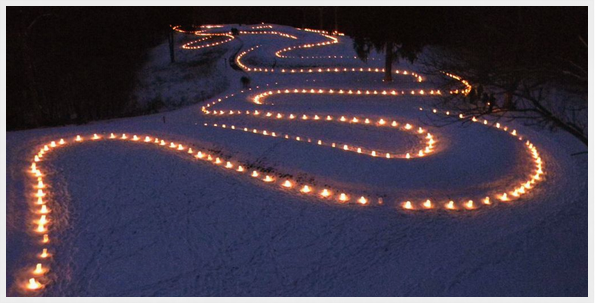

The place gets few visitors and only occasional attention from archaeologists. A nearby museum holds a few artifacts—beautiful handcrafted pieces—but most of its sourcebooks date from the late 1800s. The summer day we visited a couple of years ago, Serpent Mound gave the impression of a forgotten place. But an active community group organizes events year-round, such as a luminaria walk in December.

Building the Serpent

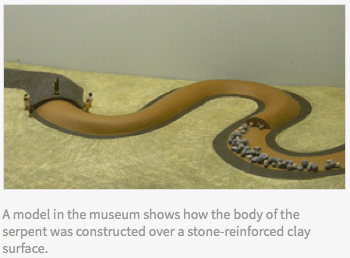

Laid out all at one time, the body of the serpent rises three feet above the surrounding land. A model inside the museum shows the cross-section: first a bed of clay and ash. Then a layer of large rocks slightly mounded. Then smaller stones filling in the gaps. Another layer of earth, and finally a layer of seeds and sod on top so that living plants might stabilize the surface.

Visiting Serpent Mound

We arrived near midday on a hot July day and began climbing the viewing tower.

At the top, the strong overhead sun disguised the serpent’s contours. Still, the scope of the serpent was impressive—too long to fit into one shot.

An evocative place

Because there are so few visitors, the park is quiet and peaceful—perfect for wandering slowly and wondering what this enormous structure meant to the Indians who built it and used it. I walked the length of it two or three times, pausing at each undulation.

Each curve of the serpent’s body encloses a small green—seven enclosures fitting within seven curves. Did people dance here? The size of each green is perfect for a small group of people. Standing within a circle, one feels surrounded, held by the serpent’s body.

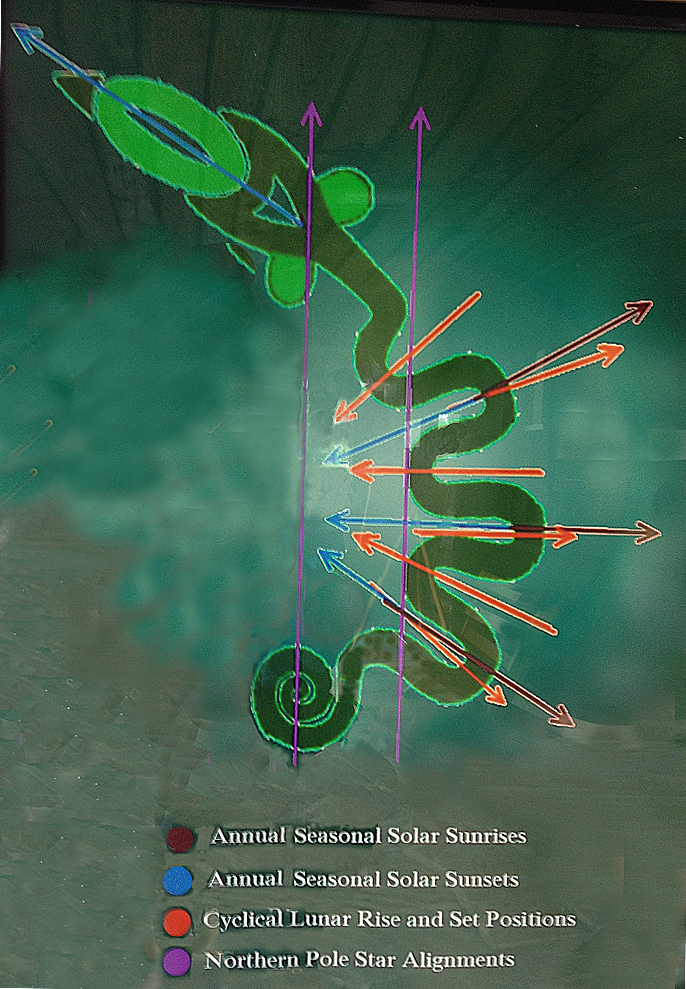

Small signposts indicate the astronomical significance of each of the curves. The serpent was built to align with sun, moon, and stars.

I searched for more information about the sky alignments, but the best I could find on-site was a laminated sheet with a huge reflective glare running down the middle (now Photoshopped out). The informality of the sheet seemed emblematic of the relative disinterest on the part of professionals in this proposed World Heritage site.

The tail of the serpent coils tightly outward from the center. I stood at the tail and wondered how the original people saw it.

Most intriguing of all is the head. Is that oval the serpent’s enormous eye? Or is the serpent holding the sun in its jaws and bearing it across the sky? Or is it carrying an egg of new life? Was it a horned serpent? Or a winged one?

The sacred imagination

There is room for viewing the effigy in many different ways. And because imagination is free, I imagined my own version.

I imagined celebrations of human life taking place in each part of the serpent. Being born in the coil of the tail, winding one’s way out from the center of the earth through the birth canal. Dancing each stage of life in one of the curves or enclosures, perhaps with close friends or cohort members. I imagined how powerful it would feel knowing, as you danced, that you were aligning your life with both earth and heaven. And finally, at the close of life, reaching the end of the land at the serpent’s head and being sent off to the heavens, to a new form of living, in the heart of the egg.

An Indian interpretation

At home I discovered I wasn’t too far from the view of Mekoce Shawnee chief Frank Wilson:

If you count the curves in the Serpent, there’s seven of them, there’s seven curves before it gets to the head. And seven, the way I was taught, for the Shawano people, is the seven gates that one must go through to reach spirituality, or enlightenment, as people call it, to become a dawan, a medicine person. So each curve, a person walked the snake. They walked the serpent. And there were certain things they had to accomplish on each curve of the snake’s back. And as they accomplished this they moved on, and when they reached the head, they reached a point where everything was completely stripped away except their spirit.

The river trail

We hiked the trail that winds down to the river below the bluff, and here are a few closing photos from that walk.

Wow, what a fascinating read, Priscilla! I especially liked the photos/illustrations you put in as you were describing this Serpent Mound. And your take on the possible symbolism, along with the Shawnee’s chief’s remarks. I suppose the pathetically limited “history” education we had in our Ohio school system was perhaps quite typical in most other areas in our country. I think I’d heard of the Serpent Mound, although likely not while in school. But I can’t seem to recall such specific details from my history classes like you did! I know that my becoming aware of the forced evictions came much, much later than in junior or high school! Thanks for posting this ever-so-interesting bit of long-ago history (like, way before 1803!). I’d like to visit that spot someday.

Gwen, you’re right, the “history” is limited all over the country. Written by the conquerors, you know? Like I said, that seventh-grade memory was oddly clear. At the time I had no idea either what had happened before 1803. It just seemed weird that nothing at all was mentioned. And I have almost no other memories from junior high!

There are ancient mounds all over central and southern Ohio, and this website gives a lot of info: http://www.ancientohiotrail.org/

Then there’s Cahokia, “America’s Lost City” near St. Louis, the first urban area on this land: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/americas-forgotten-city. I didn’t hear about it until maybe a decade ago.

Happy history traveling!