We arrived on Lopez Island in August to a cabin nestled under towering firs. Our house sits in a forest, yet crack the door and the air is fecund with salt and kelp. We are near the sea!

A few doors away, an old waterlogged stairway leads down the cliff to a small shallow bay. This morning the bay shone white under an overcast sky.

I climb down those seventy-six rickety steps almost every day, hungry for that wide view across water. In the New Mexico desert we gazed west across the Rio Grande Valley, spacious as an ocean. Here we feast on a vision of blue and hear real seawater lap-lapping at our feet.

I climb down those seventy-six rickety steps almost every day, hungry for that wide view across water. In the New Mexico desert we gazed west across the Rio Grande Valley, spacious as an ocean. Here we feast on a vision of blue and hear real seawater lap-lapping at our feet.

At high tide it fills the bay, as it did late one afternoon last week.

Shoal Bight

Our little strip of shore, I discover from a local map, is called Shoal Bight. I am getting to know Shoal Bight like a new friend. And what a complex face! A new personality in each hour and each kind of weather, a new palette every morning.

Here was the very first face I saw early one morning soon after we arrived. Smoke from wildfires burning up and down the West Coast thickened the air. The sun shone dark orange for days. Still it was beautiful.

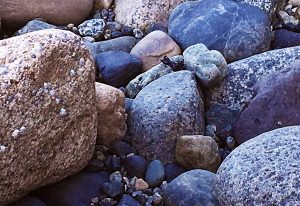

Later the air cleared, and the stones of the shoreline warmed soon after dawn in the bright sunlight of August.

Later the air cleared, and the stones of the shoreline warmed soon after dawn in the bright sunlight of August.

By September, with rains drawing near, the mornings were often tinged gray with clouds, the air heavy with mist. The sun moved south, no longer lighting the stony shore. Still it was beautiful.

By September, with rains drawing near, the mornings were often tinged gray with clouds, the air heavy with mist. The sun moved south, no longer lighting the stony shore. Still it was beautiful.

To be a bay

To be a bay

As it happens, the audiobook I am listening to as I learn to know Shoal Bight is Robin Wall Kimmerer’s luminous Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Milkweed Editions, 2013). A botanist in the Western scientific tradition, Kimmerer also teaches traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), for as a Citizen Potawatomi, she is steeped in Indigenous ways of knowing.

She writes of studying the Potawatomi language—how hard it is to learn the verbs, how complicated to conjugate them. In Potawatomi, a near relative of Ojibwe, over 70 percent of words are verbs. (Compare with English, where 30 percent of words are verbs.)

She writes of studying the Potawatomi language—how hard it is to learn the verbs, how complicated to conjugate them. In Potawatomi, a near relative of Ojibwe, over 70 percent of words are verbs. (Compare with English, where 30 percent of words are verbs.)

One night, as she pored over her Potawatomi dictionary, she grew more and more frustrated.

One night, as she pored over her Potawatomi dictionary, she grew more and more frustrated.

Pages blurred and my eyes settled on a word—a verb, of course: “to be a Saturday.” Pfft! I threw down the book. Since when is Saturday a verb? Everyone knows it’s a noun. I grabbed the dictionary and flipped more pages and all kinds of things seemed to be verbs: “to be a hill,” “to be red,” “to be a long sandy stretch of beach,” and then my fingers rested on wiikwegamaa: “to be a bay.”

She thought it ridiculous. There was no good reason for this language to be so difficult!

But then something happened inside her. With a shock that traveled down her arm and through her finger onto the page, the word wiikwegamaa came to life.

In that moment I could smell the water of the bay, watch it rock against the shore and hear it sift onto the sand. A bay is a noun only if water is dead. . . . But the verb wiikwegamaa—to be a bay—releases the water from bondage and lets it live.

In a world where all is alive, as it is among the Potawatomi, the language must be rich in verbs, for countless verbs needed to express the countless unique ways of being alive.

“To be a bay” holds the wonder that, for this moment, the living water has decided to shelter itself between these shores, conversing with cedar roots and a flock of baby mergansers. . . . The language [is] a mirror for seeing the animacy of the world, the life that pulses through all things, through pines and nuthatches and mushrooms.

Grammar of animacy

Grammar of animacy

“This is the grammar of animacy,” Kimmerer writes.

The language reminds us, in every sentence, of our kinship with all of the animate world.

For the many people who remember the aliveness of the world, the English language seems poverty-stricken. It requires all beings except humans to be referred to as “it,” robbing friends and kin such as trees or rocks—or bays—of their complex faces. To remember our cousins and friends, we need ways of communicating that allow other beings also to live. Kimmerer says it may well be the bottom line of our survival.

[T]o become native to this place, if we are to survive here, and our neighbors too, our work is to learn to speak the grammar of animacy, so that we might truly be at home.

A world of teachers and friends

Such a world is much less lonely. It’s a peopled world I’ve devoted my life to exploring and writing about. Kimmerer puts it this way:

Imagine walking through a richly inhabited world of Birch people, Bear people, Rock people, beings we think of and therefore speak of as worthy of our respect, of inclusion in a peopled world. . . . Imagine the access we would have to different perspectives, the things we might see through other eyes, the wisdom that surrounds us. We don’t have to figure out everything by ourselves: there are intelligences other than our own, teachers all around us.

Shoal Bight as teacher

So I return to Shoal Bight day after day to learn again. Some days the bay shows me how to host harbor seals. I may not have noticed these three swimming close to shore but for their soft “whuff-whuff” as they surfaced to breathe, the only sound in an exceptionally still dawn.

Most days the voice of the bay is quiet, the water lapping gently over stones. But sometimes the bay shows a choppy face and says “swish-swash” for hours on end, the water rushing back and forth quickly over rocks. It sounds like a washing machine, an enormous washer wide as the horizon. Here was a clear but choppy midmorning in early October.

Most days the voice of the bay is quiet, the water lapping gently over stones. But sometimes the bay shows a choppy face and says “swish-swash” for hours on end, the water rushing back and forth quickly over rocks. It sounds like a washing machine, an enormous washer wide as the horizon. Here was a clear but choppy midmorning in early October.

On very clear days, as on this September afternoon, Mount Baker is visible to the northeast, peeking above cloud banks.

On very clear days, as on this September afternoon, Mount Baker is visible to the northeast, peeking above cloud banks.

But perhaps my favorite hour is sunrise. And on this September morning I felt thrilled indeed to arrive at Shoal Bight just at the moment of golden light. Looking toward the left, or west, showed a forested shore radiant in the dawn.

But perhaps my favorite hour is sunrise. And on this September morning I felt thrilled indeed to arrive at Shoal Bight just at the moment of golden light. Looking toward the left, or west, showed a forested shore radiant in the dawn.

But ah! Toward the east! “To be a bay in dawn light.” We need a verb for this too.

But ah! Toward the east! “To be a bay in dawn light.” We need a verb for this too.

How beautiful !! I love the idea of “the language [is] a mirror for seeing the animacy of the world,” I can see that ! It’s a revelation to me! Wow !!! What a wonderful blog, Priscilla, thanks.

Thanks, Barbara! You being a word lover would get it! 🙂 I sure do wish the other beings of the world could live in our language too. Apparently Potawatomi doesn’t split pronouns into gender, “he” and “she.” The distinction is “animate” or “inanimate.” Only things made by humans, which do not self-generate, are inanimate.

What a beautiful place you have landed on. Thanks for sharing it.

Thank you, Kathy, and thanks for dropping by!

Such a touching journey!

Glad you enjoyed, Jennifer.