“Natural” and “supernatural” used to be easy to tell apart. The natural world followed laws of nature—in short, anything we can see and touch. The supernatural did not.

Mind-body split

The division makes sense if you accept the idea of Descartes (borrowed from Plato and the Greeks) that mind and body are separate. After Descartes, science turned to explaining nature in its own terms—finding physical causes instead of resorting to an idea of mind, or God. It was a liberating move. It freed people to trust visible cause and effect rather than appealing to some outside, unseen, capricious power.

The division makes sense if you accept the idea of Descartes (borrowed from Plato and the Greeks) that mind and body are separate. After Descartes, science turned to explaining nature in its own terms—finding physical causes instead of resorting to an idea of mind, or God. It was a liberating move. It freed people to trust visible cause and effect rather than appealing to some outside, unseen, capricious power.

But when matter was sundered from spirit, heart went out of the world. After Descartes, people whittled their idea of the natural world down to the material world only.

Where’s love?

And here lies the crux of the ecological crisis we now face.

If what is “natural” is only what can be seen and touched, where is love? Or any of the other invisible qualities, such as joy or peace, that make life worth living? Is there room for them in nature?

Not in the official story. Which is why science for four hundred years has excluded love from its methods. Feelings are separated from knowing. The mind-set of the experimenter is thought irrelevant to the results.

When animals are machines

Descartes’s move had a chilling effect within Western people, starting with Descartes himself. It is no accident that the champion of the mind-body split performed vivisection—experimenting on live animals (though he was not the first). In 1638 he reported dissecting a live rabbit to prove a point of physiology. He had decided animals were incapable of pain. Their screams were but the mechanical reflexes of automatons.

Where matter runs like a machine, love has exited the world. Love is no longer intrinsic to life. It just gets in the way.

Where matter runs like a machine, love has exited the world. Love is no longer intrinsic to life. It just gets in the way.

And this is why the retreat from spirit led directly to our current ecological crisis: not because losing an idea of God meant losing some supernatural—outside nature—enforcer of goodness or love but because people’s view of the natural world changed. Attitudes hardened. Separating spirit from matter separated the natural world from love—or any other feelings—and carved away any notion of built-in intelligence, or spirit, from nature itself.

On not catching up to Darwin

Descartes’s views have been called “monstrous.” Darwin, for one, objected strongly to the idea of animals as machines. To Darwin, humans share with at least some other animals “similar passions, affections, and emotions, even the complex ones” (Descent of Man, 1871).

But Descartes was only being consistent. When matter is a machine, love and empathy are not “natural”; they lie outside nature. The laboratory testing industry continues to follow Descartes and has never quite caught up to Darwin. Vivisection continues today.

Western societies have followed Descartes in other ways as well. In addition to science, Western medicine, economics, law, and ethics were all built on the fundamental metaphor of nature as a machine. At the root of Western thinking lurks the idea that all beings of nature—except humans—operate more like mechanisms than like intelligent, loving, striving, growing, dying organisms. The cosmos is a clockwork.

Or it was for a couple hundred years. But it was scientists themselves who mixed up the story.

The plot thickens

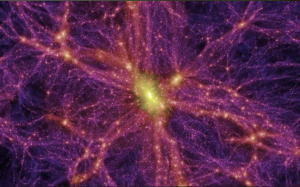

Nearly a century ago quantum theory replaced certainties with probabilities. Indeterminacy alone, according to some scientists, killed off the materialist view. But things keep getting stranger. In recent decades physicists and cosmologists talk of strings, multiverses, dark energy, dark matter—all of them invisible to human seeing though indicated by the math or inferred from their effects, such as dark matter tugging on the  A computer-generated image of dark matter’s possible distribution across millions of light-years of space. From www.bbc.co.uk. visible world through gravity. No one would suggest that these phenomena violate the laws of nature; they are not supernatural in that sense. But to someone thinking in those terms, they might look that way. They stretch older understanding of those laws and so are bringing about revisions in scientific models of nature.

A computer-generated image of dark matter’s possible distribution across millions of light-years of space. From www.bbc.co.uk. visible world through gravity. No one would suggest that these phenomena violate the laws of nature; they are not supernatural in that sense. But to someone thinking in those terms, they might look that way. They stretch older understanding of those laws and so are bringing about revisions in scientific models of nature.

Scientists today, in all seriousness, are studying invisible things. Fantastical things. Things that used to be the stuff of sci-fi only. Science writers tell us that models of nature will only get weirder, that the fundamental structure of reality may not be built on particles at all—that is, on matter—but on something else, possibly information.

Does the old natural-supernatural split make sense?

All of which troubles a great deal the old taken-for-granted split between natural and supernatural, between matter and spirit. If things don’t act thinglike anymore, if invisible realms can be objects of serious scientific study, and if the laws of nature extend far beyond the solid everyday world of the senses, does that old division make sense?

In a word, no. It came into being when the most pressing cosmological question was, Are there exceptions to material cause and effect? The question rested on mechanical physics—a limited model of nature. It rested as well on an idea of God as the exception—a limited view of spirit too.

Descartes wished to bring natural philosophy down to Earth. Yet science, that most down-to-Earth inquiry, keeps shaking things up. If science can arrive at more nuanced models of reality, why not spirituality?